|

. |

Home Cet article en français Women in colonial times Ecrivaines depuis les années 1960 |

| Keeping track of women writing |

| African penwomen of the colonial era |

Despite the emergence of a class of literate,

progressive and imaginative women who took charge of

new tasks and responsibilities in Africa during the first half of the 20th century, texts written in French by women of

African origin have been few and far between. Girls' education,

French colonial discourse and sexist prejudice contributed largely to this

state of affairs. To date, therefore, very little is known about African women's

reliance on, and contribution to the written word at that time.

As noted by historian Marie Rodet : "Colonial archives were

mostly produced by men who gave little attention to women, and only took them

into account in relation to their family and reproductive function, not as

individuals[1]. When Officialdom was interested

in the "native girl", it was primarily, as argued by Pape Momar Diop, "to train

good housewives hewed to Western ways and housework"[2].

Others factors as well contributed to the marginalisation of progressive

African women's achievements. For example, the ethnologists who scrutinised

Africa during the first half of the 20th century aimed at "describing primitive

and authentic African tribes on the path to extinction" rather than opening a

dialogue with progressive African women comfortable with Western ideas[3]. Thus, at the day of reckoning, one has to note

that, in spite of its claim to objectivity and non-discrimination, "History is

always somewhat misleading, at least by omission"[4].

Despite the emergence of a class of literate,

progressive and imaginative women who took charge of

new tasks and responsibilities in Africa during the first half of the 20th century, texts written in French by women of

African origin have been few and far between. Girls' education,

French colonial discourse and sexist prejudice contributed largely to this

state of affairs. To date, therefore, very little is known about African women's

reliance on, and contribution to the written word at that time.

As noted by historian Marie Rodet : "Colonial archives were

mostly produced by men who gave little attention to women, and only took them

into account in relation to their family and reproductive function, not as

individuals[1]. When Officialdom was interested

in the "native girl", it was primarily, as argued by Pape Momar Diop, "to train

good housewives hewed to Western ways and housework"[2].

Others factors as well contributed to the marginalisation of progressive

African women's achievements. For example, the ethnologists who scrutinised

Africa during the first half of the 20th century aimed at "describing primitive

and authentic African tribes on the path to extinction" rather than opening a

dialogue with progressive African women comfortable with Western ideas[3]. Thus, at the day of reckoning, one has to note

that, in spite of its claim to objectivity and non-discrimination, "History is

always somewhat misleading, at least by omission"[4].

The evolution of girls' schooling from a "basic and practical" approach to a more academically oriented syllabuses — that allowed the first African women to enter university in the middle of the 20th century — is part of an evolution that is only being explored very recently. Scholars such as Pascale Barthélémy[5] and others have tackled a ground-breaking exploration of the field that could "challenge our knowledge of the subject"[6]; but it still remains difficult to ascertain the extent to which colonial French schools and literacy prompted attitudinal changes such as those mentioned by Adame Ba Konaré in her dictionary of Malian women :

-

One rides her bicycle with the intent to shock the patriarchal society [...]

one goes as far as driving a car and taunting colonial bystanders as did

Marguerite Bertrant.

Some women lead the fight within unionistic and apolitical groups and associations to show their preoccupation with social progress.

When Independence was gained in the 1960s, women already constituted quite a significant powerful entity, even though they were still maintained in subservient positions[7].

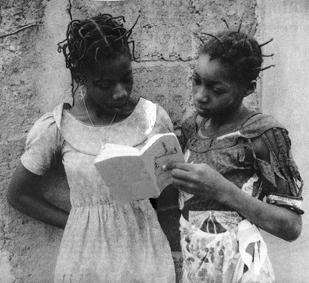

What was the importance of writing and reading to these women? How important were books to the nurses who graduated from the School of Medicine and Pharmacy that opened in Dakar in 1916? How important were they to the women teachers who attended Dakar Teaching College in Rufisque from 1938 onward ? It is difficult to tell, even if some of these women seemed to have been avid readers, as shown by Aoua Kéita in her autobiography :

-

Up to that time [1935], I was reading a lot, but mainly romance, detective

novels and medical journals...[8]

For a Black African woman, cycling, driving or even flying an aeroplane — such as Thérèse Bella Mbida (born in 1932) pictured aboard her Cessna in Rachel-Claire Okani's collection of portraits[9] — meant flouting conventions. Reading and expressing literary ambitions would have been received with the same scorn. This explains also the paucity and long-lasting lack of interest in documents, literary and otherwise, by literate women who were considered marginal. To this day, one would be hard pressed to find a single text published in French during the French colonial era by a Black African woman, bar a few short pieces of "no literary value" according to 20th century conventional wisdom.

Admittedly, the few bits and pieces available were not written out of literary

preoccupations, yet they shed light on colonial society from an African and

female point of view. New roles befell the young literate women and the letters

written by adolescents attending French colonial schools typify this evolution.

Marie Claire Matip (born in 1938) illustrates the point in her autobiography

:

Admittedly, the few bits and pieces available were not written out of literary

preoccupations, yet they shed light on colonial society from an African and

female point of view. New roles befell the young literate women and the letters

written by adolescents attending French colonial schools typify this evolution.

Marie Claire Matip (born in 1938) illustrates the point in her autobiography

:

The art of writing also offered new ways of communicating with personal friends and lovers, as shown in the following short piece by an adolescent woman from Zambia writing in the 1920s to her sweetheart :

The correspondence between Juliette and Fred — two students aspiring to become school-teachers — that was published in one of the first issues of Présence Africaine testifies, as well, to the speedy adaptation of writing to the idiosyncratic needs of young women who used it to their own advantage[12].

-

I kept thinking through the night and I tell you what, Fred, it's not your

occupation that I like; it's you, the whole of you; it's your heart that I

always loved. I encouraged you to find your calling in life, whatever it was.

You entered Teaching and I was delighted. Now, you are going to be away from me

for four years; I love you and always will the way you are; if you look for a

career change, it wont change your heart, I believe, and it wont stop me from

loving you[13].

Aoua Kéita's autobiography also mentions the author's correspondence

with her fiancé, Diawara, in 1932. Both youths had been posted far apart

by the colonial administration — "a common fate betiding local civil servants

under colonial rule"[14], she said, and short

of being able to see each other, writing letters provided an easy way to keep

in touch, though the unusual nature of the exchange did not escape locals'

attention and comments :

Aoua Kéita's autobiography also mentions the author's correspondence

with her fiancé, Diawara, in 1932. Both youths had been posted far apart

by the colonial administration — "a common fate betiding local civil servants

under colonial rule"[14], she said, and short

of being able to see each other, writing letters provided an easy way to keep

in touch, though the unusual nature of the exchange did not escape locals'

attention and comments :

-

– No my friend, the postal clerk Baba Doucouré answered [...]. At every

mail delivery there are letters going to and fro. It is I who has the

satisfaction to deliver those letter to Miss[15].

How many letters written by Aoua Kéita survive to this day? How many appeals to the Governor of the Colonies, such as the pleas sent in 1919 and 1920 by Senegalese N'della Sey for the release of her son who had been jailed for three years?[16] How many texts requested by teachers — in Mission and State schools?[17] How many poems? How many autobiographies, such as Marie-Claire Matip's Ngonda (published in1958)[18]; or the anonymous text proposed to its readership by the weekly Dakar-Jeunes in 1942 under the caption : "I am an African woman... I am twenty years old"[19]? The answer to these questions is all to easy : nobody knows exactly[20].

To get an idea of Black African writing during the colonial era, starting from its origins, one has to leave the realm of the French colonial Empire and look elsewhere.

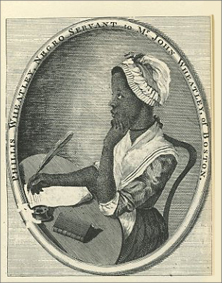

The first Black African woman writer to publish a book was the West African

Phillis Wheatey. Born in 1753, she was sold into slavery and transported to the

USA where she was bought by John and Susanna Wheatley who gave her the name of

the ship that carried her to America. The young Phillis showed, almost

immediately, exceptional intellectual faculties and learned to speak, read and

write in English in record time, following through with the study of canonical

authors of her day and writing poetry. In 1773, aged twenty, she became the

first Black women writer to publish a literary book[21].

The first Black African woman writer to publish a book was the West African

Phillis Wheatey. Born in 1753, she was sold into slavery and transported to the

USA where she was bought by John and Susanna Wheatley who gave her the name of

the ship that carried her to America. The young Phillis showed, almost

immediately, exceptional intellectual faculties and learned to speak, read and

write in English in record time, following through with the study of canonical

authors of her day and writing poetry. In 1773, aged twenty, she became the

first Black women writer to publish a literary book[21].

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., who wrote the Preface of the re-edition of the volume two centuries later, highlights the uniqueness of this collection of poems and the significance of this work :

We do know however, that the African poet's responses were more than sufficient to prompt the eighteen august gentlemen to compose, sign, and publish a two-paragraph "Attestation," and open letter "To the Publik" that prefaces Phillis Wheatley's book and "assure the World, that the Poems specified in the following pages, were [...] written by Phillis, a young Negro Girl, who was but a few Years since, brought as an uncultivated Barbarian from Africa. [...]. She has been examined by some of the best Judges, and is thought qualified to write them"[22].

As a matter of course, Phillis Wheatley had to adopt the cultural and religious beliefs of the Wheatley family and her erudition reflects the influence of both 18th century neoclassicism and the great English philosophers of her time. The titles of the poems published in her collection bear witness to the breadth of her knowledge : "To Maecenas", "On Virtue", "To the University of Cambridge in New-England", "On the Rev. Dr. Sewell", "On the Death of a young Lady of five Years of Age", etc. However, her discerning acquaintance with American wisdom did not mean that she forgot her unfortunate companions lost to the bondage of narrow-minded racists and ignorant masters. Despite her education, this issue remained close to her heart and mind as shown in various letters and poems she wrote. "On being brought from Africa to America" for example, she acknowledges Christianity's hold on her soul, but it also challenges White-America's essentialist view of the Blacks :

-

'Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,

Taught my benighted soul to understand

That there's a God, that there's a Saviour too :

Once I redemption neither sought nor new.

Some view our fable race with scornful eye,

"Their colour is a diabolic die."

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refin'd and join th' angelic train[23].

One can only wonder why the work of the first black American writer remains almost unknown, in Africa as well as in France and elsewhere; why Phillis Wheatly's collection of poems has never been readily available in a popular edition; why the bicentenary of her birth — in 1753 — and of her death — in 1784 — did not give rise to grand memorial celebrations and a wealth of studies about her life and work; and why, more than two centuries after the publication of the first book written by a Senegalese writer, this volume and the author's correspondence have not been translated and are still not available in French? The racism and the sexism that have presided over world affairs in general and French attitudes in particular, no doubt point to the answer[24].

Absentees from 18th century French literature, women of Black African origin were also missing from 19th century writing[25]. It would be interesting to learn the fate of the few African women who were sent to France to further their education; those such as Senegalese Anne Florence who appears to have been sent there in the early 1800s and died in France in 1836[26]. Did she leave behind any written fragments relating to her French sojourn? Did any other African women put pen to paper at the time? Possibly : but until documents are found, one has to look again outside France and French texts in order to evoke writing by women in the 18th century. Afro-Brazilian Maria Firmina dos Reis, for example, published one of the very first novels written by a Black women in 1859 under the title Ursula (her work written in Portuguese has not been translated so far)[27]. So too Afro-American Harriet E. Wilson, who also published a novel in 1859 under the title Our Nig; or, Sketches from the Life of a Free Black (neither available in French translation)[28].

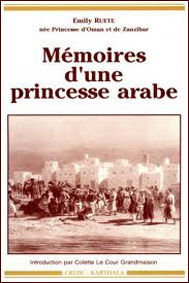

The autobiography published in Germany under the title Memoiren einer arabischen Prinzess [Memoirs of an Arabian Princess] in 1886 by the daughter of the Sultan of Zanzibar, Emily Ruete-Saïd (born in 1844), is one of the most fascinating texts written by an 18th century African woman[29]. The narrator tells of her life in her father's palace and the events that led to her leaving the island of Zanzibar and settling in Hamburg with a German businessman she had married, after eloping to Aden in 1866.

Memoirs of an Arabian Princess recounts the author's youth, the constant movement of slaves, relatives and visitors that characterized life in the Sultan's residence in Bet il Mtoni, her happy memories and the time spent with her mother, brothers and sisters. The book also mentions difficult times that punctuated life in the Palace : the intrigues, her conflict with her brother Bargash on the death of her father, the meddling of England in Zanzibar's internal affairs, etc. An astute observer of African, Arabic and European cultures, Emily Ruete-Saïd proposes also a comparative analysis of the way of life in the country of her birth and in Germany : this from the point of view of an African woman who knows them both. Needless to say, she did not share the views held by the colonial powers who proclaimed the superiority of White culture and Europe's "civilising mission". An example :

-

School is of small importance to the Oriental. In Europe the life of Church and

State is bound up with that of the schools, influencing all, from prince to

pauper. Here the individual depends very largely, both as regard the

development of his character and the hopefulness of his future prospects, upon

his scholastic career, which has so little significance in the East, and which,

to many dwellers of those parts, has no existence. Let me begin my disquisition

on this subject by describing the system in vogue at my home.

At the age of six or seven all my brothers and sisters, without exception, were supposed to commence their schooling. We girls needed only to learn reading, but the boys had to learn writing as well. [...] The lessons took place on an open veranda, to which pigeons, parrots, peacocks, and bobolinks enjoyed unrestricted access. This veranda overlooked a courtyard, so that we could amuse ourselves by watching the lively proceedings down below. Our academic furniture consisted of one enormous mat, and equal simplicity distinguished our apparatus for study : the Koran with its stand, a small pot of ink (domestic manufacture), a bamboo pen, and a well-bleached camel's shoulder blade. [...]

Besides reading and writing, a little ciphering was taught; mental arithmetic involved numbers up to one hundred, while on paper one thousand was the limit. Anything beyond these figures was regarded as pernicious. Not much store was bestowed on grammar and orthography. As for history, geography, physics and mathematics, I never heard of them at home, and not until I came here did I get acquainted with these branches of study. But whether I am really any better off for my small amount of learning, which I laboriously obtained here by dint of untiring industry, than my friends in Africa, still remains an open question to me. I can say with full veracity, though, that I was never so egregiously humbugged and brow-beaten as after acquiring the most valuable treasures of European knowledge. Oh, you happy souls over there, you cannot even dream of what may be done in the exalted name of civilisation![30]

Whereas Emily Ruete-Saïd could convey her thoughts for the benefit of future generations, an overwhelming majority of African women could not and the lack of French writing which is characteristic of the 19th century extended well into the 20th. At the collapse of the French colonial empire in the 1960s, it would have been but impossible to mention a single book of consequence published by a Francophone African woman writer. After more than a century of French occupation, so called "aid to Africa" and colonial development foisted by Paris on its colonies, the Metropole had not produced a single African woman whose reputation could come even close to that of Sierra Leone feminist Casely-Hayford (1868-1960)[31]; or that of South-African healer Louisa Mvemve who exchanged a voluminous correspondence with the South African Government during the 1910s and 20s[32]. Not one. And the autobiographies based on recollections of progressive women that were published in later years remain few and far between. Guinean Sirah Baldé de Labé is a case in point : only one of the many volumes written by that author has been published to date, by a vanity press that disappeared many years ago, making the book almost impossible to find[33]. Yet, the testimony of that pioneer of French education sent to the Ancient Peul Kingdom of Fouta-Djalloo "under French protectorate" is most important.

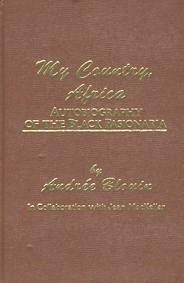

Among the small number of books published after 1960 that have recorded the voice, activities, fights and outlook on life of progressive African woman who lived and experienced colonisation during the first half of the 20th century, the autobiography My Country Africa : autobiography of the Black pasionaria[34], published in 1983 by Andrée Blouin (born in 1921), is of particular interest.

This text by a Francophone African woman was, curiously, published in English

and never translated into French. That peculiarity is symptomatic of a number

of idiosyncrasies leading to the very heart of French colonial ideology. It

explains in part the above-mentioned lack of material published in French. For

example, it was not by accident that an American woman helped the "Francophone"

Andrée Blouin to write the story of her life — in a "foreign" language —

at the beginning of the 1980s. In stark contrast to France, where the absence

of African women from the literary world was still going unnoticed, America in

the 1960s and 1970s was resolute in its determination to give a voice to Black

women of African ancestry. As Mary Helen Washington wrote :

This text by a Francophone African woman was, curiously, published in English

and never translated into French. That peculiarity is symptomatic of a number

of idiosyncrasies leading to the very heart of French colonial ideology. It

explains in part the above-mentioned lack of material published in French. For

example, it was not by accident that an American woman helped the "Francophone"

Andrée Blouin to write the story of her life — in a "foreign" language —

at the beginning of the 1980s. In stark contrast to France, where the absence

of African women from the literary world was still going unnoticed, America in

the 1960s and 1970s was resolute in its determination to give a voice to Black

women of African ancestry. As Mary Helen Washington wrote :

For America, the time had come to shake the literary establishment and to bring back to life a women's discourse that had been overlooked for two centuries. France, in contrast, remained strongly attached to the idea of literature's independence vis-à-vis social constraints. The criticism by French-Senegalese Catherine N'Diaye (born in 1952), addressed to the previous generation of African authors writing in French, illustrates the point :

-

Our writers thought they were suffering from something that was missing, she

says. They believed it to be their duty to answer a need — to fill a gap [...]

but Art cannot be born, never, from a trivial deficiency[36].

Confronted by the deafening silence of a literary community which had ignored them for as long as one could remember, Black Anglophone intellectual women changed the rules of the literary game to suit their own needs and purpose; whereas the French clung to the conventions of French intelligentsia, thus perpetuating the "trivial" absence of their fore-mothers whose education in colonial schools had never put them in a position to argue the essence of Art and the finer points of French wisdom. As was the case for many thousands of other colonised women, Andrée Blouin's path in life was not supposed to cross that of literature and it was a miracle that it did.

Born to a French merchant and an African Banziri women named Joséphine Wouassimba, Andrée Blouin fought on the side of the African Democratic Rally [RDA] in Guinea in the 1950s. She later became a leader of the independence movement in the Congo at the side of Lumumba. Yet, the education she received in Brazzaville, in a convent where she was confined by her father, between the age of three and seventeen, did not give her the writing skill that would have allowed her to write her memoirs in "transforming one's lack of being to the point where it is unrecognisable"[37], as Catherine N'Diaye puts it. Without Jean MacKellar's helping hand and interest in preserving the memory of a great African woman, hardly anyone would remember the story of the little African girl taken from her mother by her French father, imprisoned in a convent-jail in 1924 as inmate number 22 and later, blossoming into a leading political figure in her twenties[38].

At the time when Andrée Blouin was placed in the care of the Sisters, the Congo, Belgium, the Oubangui, France and the rest of the colonial world was living under the ordinance of the rigorous dichotomies that ruled society : "Black vs. White", "Mother Country vs. Colonies", "civilized vs. primitive", etc. The founding myths of colonial wisdom demanded a clear distinction between "us and them" and a racial homogeneity that could prove the supremacy of the colonisers over the colonised. Thus the proliferation of racist theories attempting to prove scientifically White superiority. As argued by Odile Tobner in her essay Du racisme français, quatre siècles de négrophobie, "the 19th century gave rise to countless racist theories published under the banner of science and many big names contributed to this collection of howlers"[39] : Paul Broca, Andress Retzius, Georges Vacher de Lapouge, Ernest Renan, Jules Ferry, Joseph Arthur de Gobineau — the author of an Essay on the inequality of human races[40] — and many others in their wake. By the beginning of the 20th century, Europe did not need convincing : it was certain of its own superiority.

The supremacy of the White imposed upon Africa at the point of the gun and confirmed by "science", had became an established belief embraced by the public at large as a matter of fact. In their eyes, not only was French colonial "effort" justified, but "the White man's burden" was also a political and moral obligation bestowed on France to civilize the "savages". These powerful myths still hold sway in many quarters of contemporary French society and gave rise to concepts such as "Cooperation" and "Francophonie". They also comforted the colonists sent to Africa to "civilize" — nowadays one would say "help" — the Africans. However, the behaviour of Andrée Blouin's father brings us down to earth and shows the fads and fancies of colonial discourse at the turn of the 20th century. To begin with, the presence of Pierre Gerbillat in Congo was neither charitable nor benevolent : he was there in order to "build his fortune in the still unknown jungles of the dark continent"[41]. Next, his behaviour was nothing short of unbecoming as he "married" a very young girl, well under age, in a remote village on the Oubangi river; this at the very time of his engagement to a Belgian women who would join him in Congo a couple of years later. His lack of interest in the fate of the little girl he fathered in his African affair was also disgraceful. So too the way he took her away from her mother in order to dump her in an orphanage where African children of white complexion were made to pay for the "sin" of their father.

Andrée Blouin's uprooting from her maternal family at an early age, her rigid education by the Missionary Sisters and her subsequent relationships with White Belgian and French colonists are in line with colonial expectations. What was not expected was the fact that she would stray from the path laid down for her by colonial officialdom and become a political activist on the side of Sékou Touré and Lumumba. As she recalls it in her autobiography :

-

For many years [...] I did not participate in the African struggle for self

determination. I could not overcome the resignation taught me by the nuns. I

bowed my head, I held my tongue, I shut myself up in the dreary passiveness of

the older women of my race.

Only when I had married — ironically, twice to white men — did I find the equilibrium and courage to become active in the cause of my people. Only then was I able to transcend my Black and White inheritance and become more than the stereotype of each. To become, simply, a woman, a human being. It was then I opted to give my life to the struggle of the blacks[42].

"To be prepared to give one's life" was not a figure of speech. Members of the RDA advocating a "No" to the Referendum, organised by France in Guinea, were met with "vexations, provocations, and attempts to intimidate us everywhere. We knew that our French opponents would not give up easily", Andrée Blouin says. Still, we were not really prepared for the extreme means they would resort to in order to silence us. Twice during the campaign I was almost killed[43]. Andrée Blouin's persecution by the French government continued after the RDA's success at the polling booths. She was forced to leave the country when her husband was dismissed from his managerial position by his company, at the request she says, of Governor Ramadier. Officials were bullying the husband in order to bring his wife into line, an expedient already tested a generation earlier on the Bonnetain family[44]. As the dust settled and a new form of colonisation was put in place, it was not the intention of Paris to encourage the publication of Andrée Blouin's account of the murky past of France, nor indeed, to expose the Republic's partners in crime. Andrée Blouin's involvement on the side of Lumumba against Belgium and other Western forces was an indictment of colonialism that "ended" with one of the most infamous episodes of the colonial era : the execution of Lumumba by agents of Belgian Intelligence.

Whereas Andrée Blouin mentions Sékou Touré's charisma to explain her initial desire to enter politics, some significant events of her life had already sensitised her to colonial oppression : first, at the age of eight, she had been traumatised, she says, by the vision of hundreds of men walking past the gate of the Convent, chained together, bloody and ruthlessly beaten by their guards who where whipping them with their chicottes. Ten years later, as she travelled across Congo with her boyfriend Roger, dumbfounded at the young man's extravagance — he even carried a little fridge to store his Perrier water and his cognac — she was abruptly drawn back to the reality of colonial life and to the haunting images of her childhood. Endless gangs of half-naked men working on the road under the watchful eye of Black guards armed with their dreaded whips, reopened an old wound and made this pitiful sight unbearable. Women and children carrying baskets of stones added to the abomination of the spectacle that drew tears to her eyes. Yet, as was the case ten years earlier, she is feeling completely powerless to do anything. This frustrated empathy with others' plight is made worse by the humiliation she has to endure herself. In the eyes of most, she remains "a native", in spite of her white skin, and she is discriminated against in the same way Black African people are : she is denied entry to the Athenakis's picture theatre, some shopkeepers refuse to sell her goods earmarked for White people, others insult her. Everything around her is a reminder of the regime of apartheid put in place by colonial powers in their African colonies. At the heart of this dehumanised universe lies the incident that possibly weighed most heavily on Andrée Blouin's decision to enter politics when an opportunity to do so would present itself : the death of her son to malaria, as the local authorities refused to authorize injections of quinine that would have saved his life : this because he was "Black" and this treatment was restricted to Whites only.

The political engagement of Andrée Blouin was not an isolated case and its origins were quite similar to that of many African militants who fought the colonial establishment in the name of freedom and social justice. The pamphlet published by Ivorian Henriette Diabaté about the 1949 women's protest march to Grand-Bassam [La marche des femmes sur Grand-Bassam] (published en 1975) is a case in point. This book evokes one of the most dramatic episodes of the fight carried out by African women against colonial abuse. Following the arrest of the leaders of the RDA and their arbitrary detention without trial for many months, thousands of women walked from Abidjan to Grand-Bassam where the prisoners were held and had begun a hunger strike[45]. Thwarting police road checks, military deployments and the Governor's best efforts to prevent them from reaching the jail, they managed to assemble in their thousands and to demonstrate their support to the prisoners. Hiding behind his gendarmes, the prosecutor refused to talk to the demonstrators and sent the armed forces to disperse the crowd. One of the few records left for posterity by a participant to that terrible ordeal is due to Mami Landji N'Dri :

-

Given the way things were panning out and fearing to be submerged, the

commissar had called for reinforcements in Abidjan. Two platoons of guards

arrived around ten o'clock with the Captains Maillet and Lemoine. They joined

in as reinforcements for the garrison that had done nothing except keep the

women in check, outside the prison. "All of a sudden there was

confusion, the military were ready to charge... Deep down I thought : we are

history, we are going to be gunned down." [...] The White man talked to us once

more : "I already told you to clear off [...] Go away !". We did not move.

[...] After the third customary warning, he drew his whistle, called the guards

and the soldiers began to push us back with their gunstocks. [...] we were

whipped into a frenzy and yelled [...]. We were pushed back to the bridge. It

was about twelve o'clock.

The police then withdrew forty security personnel and twenty guards and threw tear gas grenades at the women assembled at the Imperial Crossroad. [...] one Baoulé Nanafoué woman whose eyes were directly exposed to the gas became blind later on : many women had their bodies covered with blisters[46].

Beaten, wounded and disheartened, thousands of valiant women had to return to their homes empty-handed; no indication had been given with regard to the prisoners' fate, in spite of the women's courageous and determined action. History tells us that due judicial process was sped up as a result of their show of strength but, on the day, France was celebrating a victory, completely oblivious to the fact that their brutal repression of legitimate demands by the population had brought them one step closer to losing their grip on the colony. As M. Koffi Gadeau said at the 5th Congress of the P.D.C.I.-R.D.A., "more than the men, of whom some were ready to yield, women from Côte d'Ivoire gave the most convincing show of their political maturity and fighting spirit"[47].

Aoua Kéita's autobigraphy Femme d'Afrique. La vie d'Aoua Kéita

racontée par elle-même [An African woman. Aoua Kéita's

life told by herself] also portrays a strong, focused and very determined

personality. This book, published in 1975 is the only one of its kind in the

realm of French history and literature. It proposes a detailed account of the

professional and political engagement of an African woman in colonial times,

written by herself. Aoua Kéita was born in 1912 in Mali and sent to the

first girls' school opened by the French in Bamako. In spite of her mother's

objection to French education, she did well at school and her aptitude for

learning eventually led her to Dakar's School of Medicine where she qualified

as a nurse in 1931[48]. At first she was sent

to a small village by the colonial administration and there, she forged strong

and amicable relationships with the local women she attended and helped during

their pregnancy and childbirth. In 1935, she married M. Diawara and began to

share his interest in politics. As she recalls :

Aoua Kéita's autobigraphy Femme d'Afrique. La vie d'Aoua Kéita

racontée par elle-même [An African woman. Aoua Kéita's

life told by herself] also portrays a strong, focused and very determined

personality. This book, published in 1975 is the only one of its kind in the

realm of French history and literature. It proposes a detailed account of the

professional and political engagement of an African woman in colonial times,

written by herself. Aoua Kéita was born in 1912 in Mali and sent to the

first girls' school opened by the French in Bamako. In spite of her mother's

objection to French education, she did well at school and her aptitude for

learning eventually led her to Dakar's School of Medicine where she qualified

as a nurse in 1931[48]. At first she was sent

to a small village by the colonial administration and there, she forged strong

and amicable relationships with the local women she attended and helped during

their pregnancy and childbirth. In 1935, she married M. Diawara and began to

share his interest in politics. As she recalls :

-

Women had still not been granted voting rights. But in spite of that, Diawara

was always sharing with me his position and that allowed me to get some

interest in politics. With him, I began to follow, at some distance the

simmering tension between the Empire of Ethiopia and Italy. With him, I learned

to recognise and to condemn the aggressors[49].

Ten years later, the couple was heavily engaged with the Union Soudanaise du Rassemblement Démocratique Africain [USRDA]. Both declined the financial advantages offered to them by the French Administration and became a thorn in the side of European colonial administrators well entrenched in their privileges.

-

My European women patients who had became my friends, says Aoua Kéita,

began to put some distance between us. [...] One day, Mme Thomas, the wife of

the technician in charge of the small oil and soap factory told me :

"Madame Diawara, I think you should be careful. You have many friends amongst the Europeans because of your ability and kindness. But right now, your popularity rating and that of your husband are on the wane [...]. All that because of your political activities, it is really unfortunate"[50].

The demotions to remote disciplinary postings that followed did not diminish Aoua Kéita's activities as a political activist. In 1957, she founded an inter-union organization for women and was its representative at the inaugural Congress of the Amalgamated unions of Workers from Black Africa. The following year she was elected to the Constitutional Committee of the Sudanese Republic. In 1959 she was elected a Member of Parliament in the legislative elections and played a major political role until Modibo Kéita's downfall.

If Aoua Kéita's autobiography is depicting unambiguously the abuses of colonial rule and practices, she also takes stock of the difficulties faced by the progressive African women of her generation and their difficulty in challenging local rules and traditions. An extract of her biography recounting an incident that took place on April 8th 1959, on election day, illustrates the animosity manifested by some elders against women's power :

-

The village chief, a veteran of the French Army greeted me by shouting at me in

French, bambara and mianka :

"Get out of my village, impudent woman. You've got to be not only impudent but also insolent to pit yourself against men and in accepting the position of a man. But you have done nothing. It is the fault of these fools who lead the RDA and drag through the mud the men of this land in accepting you as their equal.

Well, well ! population of Singné. Look at that ! Koutiala, a country of valiant warriors, renowned hunters, brave veterans from the French army that would have a little woman at its head? No, it is not possible...[51]

Furthermore, political and professional commitments were often difficult to reconcile with the demands of the family who considered other priorities as more important. For example, Aoua Kéita was pressured into leaving her husband after many years of marriage as she could not bear children and her mother-in-law relentlessly asked her son to take a second wife. Summoned to choose between his wife and his mother, who was threatening to curse him, "even from the grave", if he did not take a second wife, one able to give him children, Diawara chose to obey his mother. It is interesting to note that a very similar situation is called forth by Senegalese Mariama Bâ (born in 1929) in her novel Une si longue lettre [So long a letter][52]. An interview of her compatriot and journalist Annette d'Erneville (born in 1926) — who later became the Director of Programming of the Senegalese Office of broadcasting — also hints at the difficulties awaiting intellectual women of her generation :

-

During my sojourn at Diourbel, I wrote many manuscripts which are still

unpublished. Those days had been a productive time on the intellectual front.

I was unhappy with my marriage. I was feeling very isolated. [...] I was

writing to escape from my loneliness. Writing was a kind of escape...[53]

Annette d'Erneville's comments are echoing those by Aoua Kéita when the latter says :

-

[...] solitary life was difficult to bear. [...] outside working hours and

during a good part of the night, I was reading, taking care of my garden,

knitting or sewing as I had to alter all my dresses that had become much too big

for me[54].

The following generation of women activists pressed on with the work initiated during the first half of the 20th century and made new inroads in to social and political structures. The Cameroonian Delphine Zanga Tsogo (born in 1935) is a case in point. Like Aoua Kéita, she was a nurse and, like her, she rose to the higher echelons of politics due to her militancy and commitment to women's associations. Thus, she says, her fond memory of the tremendous joy that was expressed by women around her when she became a Minister in the Cameroonian Government in 1975. Her novel L'oiseau en cage [the caged bird] shows however, that attitudes towards women did not change just because of Independence. Officially, the colonisers had left the continent, not to return, but sexism was not dead. Many African men still believed that in asserting gender equality, women forgot "God's plans and the fact that in His infinite wisdom did not create men and women as equal"[55]. In spite of increasingly progressive ideas, a great many husbands continued to claim that, irrespective of their wife's level of instruction, work, income and longing for independence, their wives needed to remember that "the subordination of women to their menfolk is an ancestral law that constitutes the fundament of our society"[56].

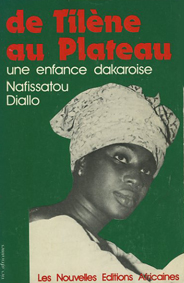

Nafissatou Diallo (born in 1941) and her autobiography, titled De

Tilène au Plateau. Une enfance Dakaroise [From Tilène to

Plateau. A childhood in Dakar], is interesting as this Senegalese author gives

a vision of traditional life that is slightly different from that pictured by the

previous writers in their books. She shows that in spite of the fact that

traditional African families of the first half of the 20th century

bestowed on fathers and husbands a far greater power than on their wives and

mothers, African society did not lack "traditional" women with a great deal of

power. Diawara's mother, mentioned above, already alluded to this category.

Mame, the grandmother who raised Nafissatou Diallo from a very early age, after

her mother died, typifies the "strong" traditional mother, loved by the

children around her and fearlessly protecting the weaker ones :

Nafissatou Diallo (born in 1941) and her autobiography, titled De

Tilène au Plateau. Une enfance Dakaroise [From Tilène to

Plateau. A childhood in Dakar], is interesting as this Senegalese author gives

a vision of traditional life that is slightly different from that pictured by the

previous writers in their books. She shows that in spite of the fact that

traditional African families of the first half of the 20th century

bestowed on fathers and husbands a far greater power than on their wives and

mothers, African society did not lack "traditional" women with a great deal of

power. Diawara's mother, mentioned above, already alluded to this category.

Mame, the grandmother who raised Nafissatou Diallo from a very early age, after

her mother died, typifies the "strong" traditional mother, loved by the

children around her and fearlessly protecting the weaker ones :

Generous, as a matter of fact, she had plenty of "grandsons", orphans, beggars and destitute foreigners to accommodate, dress and feed at our expense. My father and my uncles disapproved of her extravagance, but bent to her determination[57].

Moreover, Nafissatou Diallo's autobiography shows that the meeting of two different cultures and the experience of difference does not necessarily lead to drama, conflicts, choices and irreconcilable pledges. The narrator lost her mother when she was very young and lived in a large, polygamous family in Dakar. She was very close to her grandmother and her father and had nothing but praise for the education and opportunities she was given, both at home and at the French school. Well integrated in her traditional and caring family environment, mindful of traditional life and respectful of local religious beliefs, she had no qualms in adapting simultaneously to French ways, culture and values.

Taking life as it comes, she never surrendered her Senegalese identity and remained involved in the society around her. Like Aoua Kéita and Delphine Zanga Tsogo, Nafissatou Diallo studies nursing, marries and begins working as a nurse once she is fully qualified. This doesn't prevent her from caring for her own family and raising her children. However, in contrast to the women of an earlier generation, she does not appear to be a women out of the ordinary. She blends with the rest of Senegalese society and represents, one may say, the typical educated African woman of the second half of the 20th century; one who is in charge of her destiny and, in her stride, also takes care of the future of her continent, navigating resolutely between the many obstacles set down their path by both tradition and modernity.

The autobiographical novel "Mademoiselle" by Amina Sow Mbaye (born in 1937) conveys the same vision of the educated African women of the 1960s[58]. It tells the story of Aïda, a young Senegalese woman who, shortly after graduating, gets her first teaching position in a remote village in the north of Senegal. Full of enthusiasm and ideas, she adapts her teaching to the needs of her pupils and organises new extra curriculum activities for the local youth, such as Scouts and basketball. Like Nafissatou Diallo, Aïda marries around the age of twenty with the blessing of her family, furthers her education and enters the Civil Service where "a new life of hard work is awaiting her, split between her jobs as a woman, a mother and a Head of Department"[59]. What looked like exceptional in previous generations is slowly becoming the norm, even if this evolution once more escaped the fixed gaze of France : a France oblivious to progressive African women's role in African society.

Some of the most famous French authors of the past were led astray by the assumed wisdom of the colonial era. They lost themselves in the murky waters of racism and stumbled over shoddy scientific evidence, perpetuating to this day the same ill-informed and misconceived images of Africa and African women. Enlarging the scope of "literary preoccupations", revisiting the archives and bringing back to life documents by, and about, African women that have been long forgotten would be a first step towards debunking entrenched stereotypical images.

Jean-Marie Volet

2008

| Women's challenge to convention. The hidden face of 20th century colonial life in Africa |

Notes

[1] Marie Rodet. "Réflexions sur l'utilisation des sources coloniales pour retracer l'histoire du travail des femmes au Soudan français (1919-1946)" Etudes africaines / état des lieux et des savoirs en France. 1re Rencontre du Réseau des études africaines en France, November 2006, Paris.

[http ://www.etudes-africaines.cnrs.fr/ficheateliers.php?recordID=46] [Sighted 16 November 2007]

[2] Pape Momar Diop. "L'enseignement de la fille

indigène en AOF, 1903-1958", in AOF : Réalités et

héritage. Sociétés ouest africaines et ordre colonial

1895-1960. Dakar : Direction des Archives du Sénégal, 1995,

pp.1081-1096.

[http ://tekrur-ucad.refer.sn/article.php3?id_article=91]

[Sighted 15 January 2008]

See also Pascale Barthélémy. "Instruction ou éducation? La

formation des Africaines à l'Ecole normale d'institutrices de l'AOF de

1938 à 1958. Cahiers d'études africaines169-170, 2003.

[http ://etudesafricaines.revues.org/document205.html] [Sighted 16 November

2007]

[3] See for example ethnologist Denise Paulme's

field work in the 1930s presented by Alice Byrne in La quête d'une

femme ethnologue au cœur de l'Afrique Coloniale. Denise Paulme

1909-1998 (n.d.)

[http ://sites.univ-provence.fr/~wclio-af/numero/6/thematique/chap1Byrne.html]

[Sighted 12 January 2008]

[4] Odile Tobner. Du racisme français. Quatre siècles de négrophobie. Paris : Les Arène, 2007, p.258.

[5] See Pascale Barthélémy. Femmes, africaines et diplômées : une élite auxiliaire à l'époque coloniale. Sages-femmes et institutrices en Afrique occidentale française (1918-1957), thèse de doctorat d'histoire, Université Paris 7-Denis Diderot, 2004, 945 p.

[6] Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch. "African

Studies in France". H-AFRICA Africa Forum, 27 August 2001.

[http ://www.h-net.org/~africa/africaforum/Coquery-Vidrovitch.html] [Sighted 26

January 2008]

[7]

Adame Ba Konaré. Dictionnaire des femmes célèbres du

Mali. Bamako : Editions Jamana, 1993, pp.54-55.

In her autobiography, Aoua Kéita wrote also with regard to the year 1949 : "A good deal of my Sunday afternoons were occupied with cycling outings ...".

Aoua Kéita. Femme d'Afrique. La vie d'Aoua Kéita

racontée par elle-même. Présence Africaine, 1975,

p.79.

[8] Aoua Kéita. Femme d'Afrique..., p.45.

[9] Rachel-Claire Okani. Hommage à la femme camerounaise.Yaoundé : Editions CIAG, 1995, p.40.

[10] Marie-Claire Matip. Ngonda. Paris : Bibliothèque du jeune Africain, 1958, p.21.

[11] Mentioned by Marthe Kuntz, (Missionary in Zambèze around 1913), in her book Terre d'Afrique. Notes et Souvenirs. Paris, Société des Missions Evangélique, 1932, p.78.

[12] Charles Béart. "Intimité :

lettres de la fiancée", in Présence Africaine 8-9, 1950,

pp.271-288.

Pascale Barthélémy mentions as well the minutes of a meeting from

l'Ecole normale dated May 6 1947 that says : "some months later, the

disciplinary committee decided to expel a third year Camerounian student who

had covert relationship with a male youth, and using illicit and unsuspected

means of communication. [...], X took advantage of a recent funeral service

[...] to exchange and receive letters with male correspondents". "Instruction

ou éducation? La formation des Africaines à l'Ecole normale

d'institutrice de l'AOF de 1938 à 1958". Cahiers d'études

africaines 169-170, 2003.

[http ://etudesafricaines.revues.org/document205.html] [Sighted 16 January 2008]

[13] Charles Béart. "Intimité...", p.288.

[14] Aoua Kéita. Femme d'Afrique..., p.45.

[15] Aoua Kéita. Femme d'Afrique..., p.34.

[16] "Lettre 1 and Lettre 2" [1919 et 1920] in Esi Sutherland-Addy et Aminata Diaw. Des femmes écrivent l'Afrique : l'Afrique de l'Ouest et le Sahel. Paris : Karthala, 2007, pp.242-243.

[17] Such as "Ma petite patrie", a few pages by Senegalese Mariama Bâ (born in 1929) written by the author in 1943, at the time she was admitted Rufisque Teachers College.

[18] Marie-Claire Matip. Ngonda. Paris : Bibliothèque du jeune Africain, 1958.

[19] Anonymous. "Je suis une Africaine...J'ai vingt ans" in Dakar-Jeunes no 10, 12 March 1942, p.11.

[20] An email addressed to Charles Becker by Pascale Barthélémy on January 24, 2008, suggests that more texts were written in French by African woman than usually thought, thus the necessity to look for them and to study their meaning : "... Frida Lawson, about whom I have little information [...], wrote a lot during her years in which she studied at Rufisque. She has a very personal "writing style" that is recognisable in the reports she wrote for the Head Mistress (Germaine Le Goff) of whom you have probably heard (She ran Rufisque between 38 and 45 and I wrote an article about her in tribute to Catherine Coquery). Frida Lawson was in charge of conducting the expeditions organised to return the students to their families during the summer holiday. I photocopied many of her accounts as she was traveling across the AOF and analysed them in my thesis, but these documents would need further examination".

[21] "Without any Assistance from School Education, and by only what she was taught in the Family, she, in sixteen Months Time from her Arrival, attained the English language, to which she was an utter Stranger before, to such a Degree, as to read any, the most difficult Parts of the Sacred Writings, to the great Astonishment of all who heard her. John Wheatley (1772)". "Letter sent by the author's Master to the Publisher", in Phillis Wheatley. Poems on various subjects, religious and moral. London : A. Bell, 1773, p.vi.

[22] Henry Louis Gates, Jr. "Foreword. In her own write", in John Shields (ed.) The collected works of Phillis Wheatley. New York : Oxford University Press, The Schomburg Library of Nineteenth Century Black Women Writers, 1988, pp.vii-ix.

[23] Phillis Wheatley. Poems on various subjects... p.18.

[24] See Odile Tobner. Du racisme français. Quatre siècles de négrophobie. Paris : Les Arène, 2007.

[25] A few African women wrote in local vernacular in 19th century and some extracts of their texts are available in English translation in the monumental anthology Women writing Africa : The southern Region. Johannesburg : Witwatersrand University Press, 2003, 554p. Some Afro-American authors such Susie King Taylor, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper and others are also worth reading.

[26] Mentioned in Kelly Duck Bryant. "Black but not African : Francophone Black Diaspora and the Revue des Colonies 1834-1842". Internationnal Journal of African Historical Studies vol. 40, no 2 (2007), pp.274-75.

[27] Maria Firmina dos Reis. Ursula, 1859. [Book not sighted]

[28] Harriet E. Wilson. Our Nig; or, Sketches from the Life of a Free Black. Boston : Geo. C. Rand & Avery, 1859. [Republished by Vintage Books, New York, 1983. Preface by Henry Louis Gate Jr and commentary by Barbara A. White]

[29]

French translation : Emily Ruete. Mémoires d'une princesse

arabe. Paris, Karthala, 1991.

English translation : Emily Ruete (Salamah bint Saïd; Sayyida Salme,

Princess of Zanzibar and Oman) Memoirs of an Arabian Princess.

Translated by Lionel Strachey. New York : Doubleday, Page and Co., 1907, n.p.

[http ://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/ruete/arabian/arabian.html]

[Sighted 19 November 2007]

See also the note by Joachim Duester, Oman Studies, 2001. [http ://www.counterpunch.org/pipermail/oman-l/2001-February/001090.html] which

includes several reviews of this work. [Sighted 22 November 2007]

[30] Emily Ruete, Memoirs of an Arabian Princess... 1907, chapter IV, n.p.

[31] See [http ://www.sierra-leone.org/heroes6.html] [Sighted 21 February 2008]

[32] Catherine Burns. "Les lettres de Luisa Mvemve". in Karin Barber (ed.) Africa's Hidden Histories. Everyday Literacy and Making the Self. Bloomington : Indiana University Press, 2006, pp.78-112.

[33] Sirah Baladé de Labé. D'un Fouta-Djalloo à l'autre. Paris : La Pensée Universelle, 1985. I have been looking unsuccessfully for a copy of this book for twenty years and could only read it at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

[34] Andrée Blouin, in collaboration with Jean MacKellar, My Country Africa autobiography of the Black pasionaria. New York : Praeger, 1983.

[35] [http ://www.library.ucsb.edu/subjects/blackfeminism/ah_langlit.html] [Sighted 19 November 2007] (Mary Helen Washington. Invented Lives : Narratives of Black Women (1860-1960), 1987).

[36] Catherine N'Diaye. Gens de Sable. Paris : POL, 1984, p.159.

[37] Catherine N'Diaye. Gens..., p.160. My translation from the French.

[38]

One may also contrast Jean MacKellar's effacement behind Andrée Blouin

(the latter tells her story as a first person narrative and signs the book)

with Ludo Martens' affirmation of himself in telling the life story of

Léonie Abo, as a third person narrative under his own name.

Léonie Abo was Mulele's wife and she followed him throughout the

popular insurrection that troubled Congo between 1963 and 1968. In a personal

communication, Mrs Abo speaks of "her" book and it is sad that Ludo Martens did

not step out of the limelight in order to offer the person he was befriending

with an opportunity to write her own story, under her signature, as a first

person narrative.

Ludo Martens. Une femme du Congo. Bruxelles : Editions EPO, 1991.

[39] Odile Tobner. Du racisme français, pp.149-150.

[40] Arthur de Gobineau. Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines [1853-1855], in Œuvres 3 vols. Paris : Gallimard, 1983-1987.

[41] Andrée Blouin, My Country Africa, p.4.

[42] Andrée Blouin, My Country Africa, p.4.

[43] Andrée Blouin, My Country Africa, p.185.

[44] [http ://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/colonie_19e_dard_fr.html#fn17]

[45] Bernard Dadié described his imprisonment in Carnet de prison. Abidjan, CEDA, 1984.

[46] Henriette Diabaté. La marche des femmes sur Grand-Bassam. Abidjan-Dakar : Nouvelles Editions Africaines, 1975, pp.50-51.

[47] Henriette Diabaté. La marche des femmes..., p.58.

[48] An article by Pascale Barthélémy titled "Sages-femmes africaines diplômées en AOF des années 1920 aux années 1960" in Anne Hugon, Histoire des femmes en situation coloniale : Afrique et Asie, XXe siècle. Paris, Karthala, 2004, pp.119-144 , proposes an interesting overview of the students' training and activities at the Ecole de médecine de Dakar.

[49] Aoua Kéita. Femme d'Afrique..., p.46.

[50] Aoua Kéita. Femme d'Afrique..., p.71.

[51] Aoua Kéita. Femme d'Afrique..., p.389.

[52] Mariama Bâ. Une si longue lettre. Dakar : Les Nouvelles Editions Sénégalaises, 1979

[53] Mentioned by Pierrette Herberger-Fofana in Littérature féminine francophone noire. Paris : L'Harmattan, 2000, p.375.

[54] Aoua Kéita. Femme d'Afrique..., p.79

[55] Delphine Zanga Tsogo. L'oiseau en cage, Paris : NEA : Edicef, 1983, p.4.

[56] Delphine Zanga Tsogo. L'oiseau en cage, p.7.

[57] Nafissatou Diallo. De Tilène au Plateau. Une enfance Dakaroise. Dakar : Les Nouvelles Editions Sénégalaises, 1975, p.16.

[58] Amina Sow Mbaye. "Mademoiselle" Dakar : NEA-Edicef jeunesse, 1984.

[59] Amina Sow Mbaye. "Mademoiselle", p.157.

Editor ([email protected])

The University of Western Australia/French

Created : 28 February 2008

http ://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/colonies_20e_eng_afr.html