|

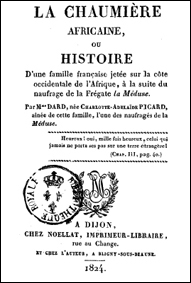

NOT TO BE MISSED "La Chaumière africaine" by Charlotte DARD. An autobiography (1824). Re-edition : Paris, L'Harmattan, 2005. (155p.). ISBN: 2-7475-8096-2. Introduction by Doris Y. Kadish.

|

Ce compte rendu en français |

First published in 1824, La chaumière africaine (The African cottage) by Charlotte Dard-Picard, provides a fascinating account of the author's life in Senegal at the very beginning of French colonial expansion in Africa. This significant piece of French history only resurfaced recently after a long hibernation in the inner sanctum of the French National Library. A substantial introduction by American scholar Doris Y. Kadish precedes the 2005 re-edition.

It is indeed a miracle that Charlotte Dard lived to tell the tale of her sojourn in Saint-Louis. The frigate "La Méduse" on which she embarked in Rochefort, was under the command of a rogue Captain who wrecked his vessel off Mauritania, abandoned his ship and left the bulk of his passengers to their fate. They were refused access to the lifeboats which were secured by the new Governor of the Colony for his entourage and abandoned on a foundering ship. It was only fate that allowed the Picard family, in the nick of time, to embark in an overloaded lifeboat instead of on a makeshift raft, hastily built by the sailors and later abandoned to the elements with hundreds of people aboard. Life on Charlotte's lifeboat was only marginally better: water and food were severely restricted, the heat intense, the vessel taking water, while a frightening storm engulfed the frail wherry, threatening to send them all to the bottom of the sea. And when the shipwrecked party eventually reached the barren coast of Mauritania, their ordeal was far from over.

It is indeed a miracle that Charlotte Dard lived to tell the tale of her sojourn in Saint-Louis. The frigate "La Méduse" on which she embarked in Rochefort, was under the command of a rogue Captain who wrecked his vessel off Mauritania, abandoned his ship and left the bulk of his passengers to their fate. They were refused access to the lifeboats which were secured by the new Governor of the Colony for his entourage and abandoned on a foundering ship. It was only fate that allowed the Picard family, in the nick of time, to embark in an overloaded lifeboat instead of on a makeshift raft, hastily built by the sailors and later abandoned to the elements with hundreds of people aboard. Life on Charlotte's lifeboat was only marginally better: water and food were severely restricted, the heat intense, the vessel taking water, while a frightening storm engulfed the frail wherry, threatening to send them all to the bottom of the sea. And when the shipwrecked party eventually reached the barren coast of Mauritania, their ordeal was far from over.

Upon reaching Saint-Louis in disarray and completely exhausted, they soon realised that the new French Governor who had behaved dishonourably during the rescue efforts was also very slow in organising relief for the survivors. It was eventually the English Governor who provided effective assistance, side-lining his French counterpart. These early shortcomings of the new French administration were heralding what was to follow and they were to plague the life of the Picards for the duration of their stay in Senegal. Because Charlotte's father did not see eye to eye with the Governor and his administration, he was systematically refused help, thus the many setbacks, reversals of fortune and hardship that often left the family destitute and on the brink of starvation.

This, of course, had a major influence on Charlotte's life, especially after the passing of her father's second wife in 1817, a loss that put her in charge of raising her younger siblings. M. Picard's commercial ventures aimed at supplementing his modest income did not bring the anticipated result: not only did they send him broke, but they also led him to lose his position in the French civil service and his regular source of income. Faced with the prospect of starvation, Charlotte had to leave for Safal, a small island on the Senegal River bought by Charlotte's father during his earlier sojourn in the country. There she endeavoured to grow enough food to feed the family and to harvest whatever cotton could be saved from the bankrupt cotton plantation of her father. For months she toiled in the fields with her brothers and sisters, surviving on a staple of a vegetables and millet cake, roughly baked over an open fire on an iron shovel. As the years went by, life on the island was punctuated by sickness and high drama that periodically reduced the family endeavours to naught, eventually leading everyone to the grave, except Charlotte, one of her sisters and a distant cousin, all of whom left the colony at the end of 1820.

The extraordinary destiny of Charlotte Dard and the positive spin she gives to her story already justifies the attraction of this autobiography. Yet there is another good reason to appreciate this book: it is a unique contribution to our understanding of the early days of French colonisation in West Africa that debunks a few myths. For example, it is striking that the fall from grace of the Picard family was the result of an ideological rather than economic clash with the Government: one not interested in bringing about new reciprocally beneficial relationships with the local population, but rather one bent on continuing to enslave African populations under a new guise. The Picard's example, values and modus operandi were indeed a thorn in Governor's side.

The mingling of people of different backgrounds that characterised the Picard's family was possibly the first bone of contention. In her introduction to the volume, Kadish mentions, in a footnote, that "four of Picard's children were those he fathered in his relationships with 'diverse women of colour' during his first stay in Senegal"(p.ix). The fact that Charlotte, her sisters, half-sisters, brothers and cousins born to White and Black mothers were all living happily together did not suit the old racist theories propagated to justify the separation of races. Moreover, they were seen as disproving all the "new scientific evidence" that highlighted the lethal dangers of racial inter-mixing that would become one of the pillars of colonial "wisdom".

Picard's refusal to punish absconding slaves who attempted to return to their family and Charlotte's compassion for those men striving to recover their lost freedom were also at odds with the tyrannical demands of colonial society. So too was the acknowledgement of Black families' generosity and genuine support when they needed it most. It is unquestionably difficult to gauge the extent of the Picard family's understanding of their Black neighbours on the sole basis of Charlotte Dard's autobiography. But the narrator and her father's readiness to share, rather than impose their views upon a significant 'Other', their determination to engage in meaningful exchanges and collaboration rather then plainly exploitative ventures, bore the seeds of a new vision of "globalisation": one that France is still reluctant to acknowledge today.

It is thus not that surprising that Charlotte Picard should have married Jean Dard, the first French teacher of the colony whose philosophy of teaching, according to Kadish, was to use Wolof as well as French with his pupils in order to provide Senegalese youth with an alternative means to explore not only European religion and science, but also the fabric of their own society. (pp.xxv-xxvi) Sharing knowledge with others, both African and European, was central to Jean Dard's educational endeavours and that, of course, was incompatible with French colonial ideology.

La chaumière africaine offers a portrait of a strong and determined young woman who displays great strength and determination in the face of adversity. Far from proposing a melodramatic and embellished account of her exploits, this autobiography eschews the stereotyped "wisdom" of the times and offers a different, unconventional and challenging take on French history. As Kadish fittingly concludes her introduction to the volume: "Charlotte Dard is indeed one of the many voices of French women of centuries past that one should definitely heed". (p.xxxvi)

Jean-Marie Volet

[Other books] | [Other reviews] | [Home]

Editor ([email protected])

The University of Western Australia/School of Humanities

Created: 6-Jan-2009.

https://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/revieweng_dard09.html