|

. |

Home Cet article en français Women in colonial times |

| ADDENDUM |

| Mme Dard, the shipwreck of the Medusa in 1816 and the early colonisation of Senegal |

It is always interesting to find out what other readers are making of

the work written by little known authors who can only be assessed from one's

own intuition. Thus my pleasure in discovering Françoise Lapeyre's

interesting study, titled Le roman des voyageuses françaises (1800-1900) [The

novel of French women travellers (1800-1900)], that proposes a wide overview of

French women who were "swept along by 19th century dynamics of knowledge

expansion"[1]. The achievements of these

travellers bound for Africa, Asia, Oceania and America, provide a unique

reflection on 19th century French preoccupations, mentalities,

perceptions of the world, hierarchies and socio-cultural divides.

It is always interesting to find out what other readers are making of

the work written by little known authors who can only be assessed from one's

own intuition. Thus my pleasure in discovering Françoise Lapeyre's

interesting study, titled Le roman des voyageuses françaises (1800-1900) [The

novel of French women travellers (1800-1900)], that proposes a wide overview of

French women who were "swept along by 19th century dynamics of knowledge

expansion"[1]. The achievements of these

travellers bound for Africa, Asia, Oceania and America, provide a unique

reflection on 19th century French preoccupations, mentalities,

perceptions of the world, hierarchies and socio-cultural divides.

Among the many books mentioned by Françoise Lapeyre, The African cottage or the story of a French family thrown on the western coast of Africa after the frigate Medusa was wrecked by Charlotte-Adélaïde Dard[2] has been of particular interest to me because it speaks volumes to the material lost to the worlds of literature and history for reasons beyond "the institutionalised gender imbalance that permeated everyone's mind"[3].

Published in 1824, The African cottage provides a firsthand account of

France's occupation of West Africa at the very beginning of French colonial

expansion. It is thus a central piece of French colonial history[4]. However, as

was the case of the writings by Mme de Noirfontaine and Mme Bonnetain, Mme

Dard's account of her experience was dismissed, not so much because it was

written by "a poor woman who knew nothing, understood little and displayed

even less imagination"[5], but rather because the author

contradicted the wisdom of the day and represented a nuisance to the

government. In other words, this testimony was not overlooked because of "the

power of archaic cultural beliefs asserting the primacy of the masculine over

the feminine"[6] – even though ingrained sexism facilitated its exclusion – but rather because the subversive, or at least unsettling nature of

the narrative was perceived as a threat to the precarious equilibrium that

sustained the lives and reputation of some influential individuals.

Published in 1824, The African cottage provides a firsthand account of

France's occupation of West Africa at the very beginning of French colonial

expansion. It is thus a central piece of French colonial history[4]. However, as

was the case of the writings by Mme de Noirfontaine and Mme Bonnetain, Mme

Dard's account of her experience was dismissed, not so much because it was

written by "a poor woman who knew nothing, understood little and displayed

even less imagination"[5], but rather because the author

contradicted the wisdom of the day and represented a nuisance to the

government. In other words, this testimony was not overlooked because of "the

power of archaic cultural beliefs asserting the primacy of the masculine over

the feminine"[6] – even though ingrained sexism facilitated its exclusion – but rather because the subversive, or at least unsettling nature of

the narrative was perceived as a threat to the precarious equilibrium that

sustained the lives and reputation of some influential individuals.

The African cottage tells the story of the author and her family. In 1816, aged 18, she left France for Senegal with her father, stepmother, brothers and sisters, aboard the frigate Medusa. When the ship ran aground, she witnessed the confusion that followed and, after a perilous few days aboard a small lifeboat and a long walk in the African desert, she eventually reached Saint-Louis where her family settled down. This book is teeming with enthralling comments about early 19th century France, the shipwreck of the Medusa and life in the colonies in the very early stage of French colonisation. Moreover, it offers a take on society that illustrates with spontaneity and simplicity the superficiality of the myths that has sustained, not only the social values, but also the honour of the Nation, socio-economic wisdom and European expansionism aimed at "developing" Africa by exporting Western civilisation to its shores.

In her preface, Mme Dard argues that her decision to put pen to paper was only due to her father's last wishes : his hope that his "persecutors" would be exposed and the misfortunes of the family brought to light "so that they would not be forgotten" (p. ij)[7]. However, the significance of the narrator's revelations, eight years after the loss of the Medusa and four years after she left Senegal, went far beyond the mere tale of a young woman recounting her tribulations in the colonies. It was published on the heels of another book by Henry Savigny and Alexandre Corréard that divided public opinion and it was not the intention of the government to reopen a damaging controversy[8]. Furthermore, England had relished the opportunity to stir up trouble in providing unconditional support to the victims of the shipwreck at the very time France attempted to quell their complaints and, in the eyes of the Government, Mme Dard's pro-English attitude was further proof of the seditious nature of her writing. Like Savigny and Corréard, whose book had been translated and published in English in London in 1818, Mme Dard's book was arguing, most convincingly, that the high moral ground was not held by the French :

-

At the moment of their separation, Major [Peddie] was eager to give to Mr.

Corréard the mark of true friendship, not only by his inexhaustible

generosity, but also by good advice [...] The following is pretty nearly the

discourse which the good Major addressed to Mr Corréard at their last

interview : « Since your intention, » said he, « is to return

to France, allow me, first of all, to give you some advice; [...] I know

mankind, and without pretending exactly to guess how your Minister of Marine

will act towards you, nevertheless, I think myself justified in presuming that

you will obtain no relief from him; for, remember that a minister, who has

committed a fault, never will suffer it to be mentioned to him, nor the persons

or things presented to him, that might remind him of his want of ability;

therefore, believe me my friend; instead of taking the road to Paris, take that

to London[9].

Nowadays, a lengthy colonisation of Senegal has allowed France to establish preferential links between Dakar and Paris, but the relationship between the two countries was quite different in 1816. England had just agreed to return Saint-Louis to France after occupying the city for several years and it was the purpose of the Medusa's voyage to convey hundreds of French troops, the new governor, Colonel Schmaltz, and the civil servants who were to reclaim the colony. The Medusa was thus sailing towards a city that was still under British administration and the French Governor's intention was to escort the English out of the colony at the earliest opportunity after his triumphal entry into Saint-Louis. The loss of the Medusa put this plan into turmoil as the French contingent was dispersed and reached the African shores in total disarray and deprived of a good number of the army personnel butchered by their own during the tragedy. As mentioned by Gaspard-Théodore Mollien in his own account of the disaster : "What pitiful a shape we were upon landing on African soil where we were expected to take over as Masters"[10].

This undignified arrival was exacerbated by the new Governor's poor behaviour during and after the catastrophe. Colonel Schmaltz was among the dignitaries embarked on the Medusa and his performance, when his leadership was needed, had been dismal. Preoccupied with his own safety, he did not hesitate to abandon women and children aboard the Medusa and to disappear with his family and close friends aboard a lifeboat he had commandeered. That, of course left an enduring imprint in Mme Dard's mind :

-

The rushed manner in which one hundred and fortyeight unlucky souls were

coerced to step down onto the raft led to the failure of providing them a single

piece of biscuit; thus the subsequent attempt to throw them a bag that

contained about twentyfive pounds of them, as they were drifting away from the

frigate, fell into the sea and it was only after considerable effort that it

could be rescued from the water.

As this disaster was unfolding, His Excellency the Governor of Senegal, whose sole preoccupation was to save his own skin, was seated in his armchair and carefully transferred to his large life-boat that was already well-stocked with large trunks, all kind of food supplies, his precious friends, his wife and his daughter.

[...]

Almost all the officers, passengers, employees and seamen were already disembarked while our tearful family was still waiting on the wreckage of the frigate for a charitable person who would accept us in one of their craft. [...]

I was calling at the top of my voice to the leaders in the vessels who were abandoning us, begging them to take our poor family with them. A short while thereafter, the large boat occupied by the Governor and his family came closer to the Medusa, as if they were going to embark a few more passengers as they were far from being overloaded. I then expressed my wish to step on board, hoping that Mmes Schmaltz, who had showed much interest in our family circumstances during the journey, would make some room for us in their boat. But I was mistaken : after quietly sliding into their boat, these ladies had already forgotten us. (pp. 50-52)

Understandably, when Colonel Schmaltz arrived in Saint-Louis with his family, four days ahead of the others, his main preoccupation was to erase the evidence of his disgrace. Typifying the kind of rogue character described by Major Peddie to Corréard, he baulked at nothing and in his denials seemed unperturbed by unexplained coincidences :

-

Fifty two days after the abandonment of the castaways, only three men were

found on the remains of the Medusa, and not much of men either, rather barely

living skeletons. Two of the three poor souls who were saved from the wreck died

a few day after they arrived in the Colony and the third, who professed knowing

many incidents of the Medusa abandonment, was murdered in his bed, while in

Senegal, shortly before he was due to return to France. The authorities could

not find the assassin who did not steal anything from his victim after

murdering him. (pp. 58-59).

The Picard family was among the disquieting witnesses to be silenced and Colonel Schmaltz provided them with no material support when they eventually made it to Saint-Louis. Destitute and abandoned, Mr Picard then turned for help to Major Peddie, the English Governor. Unlike Colonel Schmaltz, the former had made the trip from his headquarters in order to welcome the survivors and showed a great deal of compassion for the women and children who had been victims of such a terrible ordeal. Upon reading Mme Dard's glowing portrayal of Major Peddie, the French Government could be excused for believing that she was deliberately provocative in underlining the gap that separated a good-natured and yet determined English gentleman[11] from a two-faced French colonel with no regard for etiquette and proper behaviour : the English Governor had been a man of action who had sent the worst affected to hospital and invited the English settlers to show compassion to the new arrivals. One of the consequences of this benevolence meant that the narrator and her sister were invited to share the abode of an English family :

-

Once at Mr Artigue's place, we met his wife, two young ladies and an English

woman who begged us to accept her hospitality. She then took my sister Caroline

and I to her house where she introduced us to her husband who welcomed us very

graciously... (p. 156)

The way things were unfolding did not follow the scenario planned in Paris. After the severe military humiliation suffered in conflicts with Britain in 1815 and a treaty that was not favourable to France, despite the return of Senegal and a few other territories to France, it was time for the new French government to show that the country was again on the ascendancy : that it had lost nothing of its determination, that it remained a world leader and a reference point in terms of refinement and sophistication. Mme Dard's contrasting portraits of Major Peddie and Colonel Schmaltz did not fit the French high aspirations. Rather they were an embarrassment as they called into question the honour and the integrity of a French army officer and, by association, of the whole French Army. That alone would have been enough to exclude Mme Dard's book from any list of recommended reading, but there was more bad news.

Unfortunately for the French administration, and for the literary future of Mme Dard, people called to answer for the trauma suffered by the Picard family did not stop at Colonel Schmaltz. The Viscount de Chaumareys, Captain of the Medusa, was also sitting in the dock of the accused. According to his fellow officers, he was unfit to lead his crew. He had not sailed for the previous twenty years and had been appointed on the strength of his name rather than his seamanship. Following the decommissioning of numerous Bonapartist officers, the Ministry of Marine had recalled a number of survivors from the Ancien régime, paying little attention to their professional credentials. The Viscount de Chaumareys was one of them, but he was not ready to admit his incompetence thus his stubbornness, lack of judgment and a complete disregard of the advice given to him by fellow officers much better qualified than he. To Mme Dard, there was but one person responsible for running the Medusa aground and that was the captain :

-

At about 10 in the morning, the captain was made aware of imminent danger and

was urged to change the course of the frigate to the west because of the risk

of running aground on the reefs of Arguin; but this advice was scorned and the

predictions mocked. One of the officers of the frigate [...] was put under

arrest. (p. 50)

During the stormy meetings that followed the announcement of the catastrophe in Paris, the Minister of Marine was rightly accused of having compromised safety by showing favour to incompetent members of the Ancien régime. However, this heated argument would have died if it had been possible to show that Captain de Chaumareys had been able to redeem both himself and the honour of the French Navy by some heroic deeds. Unfortunately, reports to the contrary were running wild that the Captain of the Medusa had fled the scene of the disaster aboard a lifeboat, abandoning many people on board the vessel and leaving the rest, including those piled up aboard a makeshift raft, to fend for themselves. As mentioned by Corréard in his book, this did not go well with the witnesses to this infamy :

-

Eventually, M. de Chaumareys embarked onto his life boat by a manoeuvre at the

bow : a few sailors rushed there and cast off the moorings that were tying it

to the frigate. Straight-away, the screaming from those men left rose twice as

loud, and M. Danglas, an officer of the Infantry, even took a rifle to shoot

the captain, but he was restrained.

The way M. de Chaumareys abandoned all the people around him confirmed that he was of poor character, as had already been noticed during the voyage. The cowardice he displayed at this critical time, in betraying all his responsibilities, was not only contravening the obligations of his position, but also the most sacred rights of humanity : a point met with a general burst of indignation[12].

That indignation was shared by the Dard family who learned to its cost that the captain of the frigate, like the Governor, could not be trusted and would not come to their rescue. And those showing courage and determination, Mme Dard says, were the very same people who had attempted to avoid the tragedy in the first place and who were now left to deal with the situation in the context of their commanding officer's desertion.

-

Shortly after M. Lachaumareys embarked, despite the fact that more then sixty

people were still aboard the Medusa, the brave and generous M. Espiau,

commanding officer of the longboat, left the other vessels and returned to the

frigate, intent on saving all the poor souls who had been abandoned there. (p.

58)

Given the fact that the death penalty was to apply to "every commanding officer found guilty of abandoning his vessel while there were still other people aboard"[13], it was difficult to explain the leniency of the Naval Court Martial which sentenced the cowardly captain to three years jail and to his removal from the Roll of French Naval Officers. Yet, as was the case with Colonel Schmaltz's reprehensible behaviour, it was not in the interest of the State to make too much fuss about this shameful incident. Corréard was probably right when he suggested that "there is, among the naval officers, an uncompromising esprit de corps, a so-called matter of honour, as mistaken as it is peremptory, that pushes them to consider as insulting to the whole of the Navy the unmasking of a culprit"[14]. Resurrecting the deeds of a naval officer who was better forgotten outraged the Navy and exposing the true colours of Colonel Schmaltz was a slap in the face for the Army. Thus, not surprisingly, Mme Dard's testimony never made it to mainstream historical accounts of the Nation.

And, as if the behaviour of the leaders put in command by the State did not suffice to discredit the Nation and her quest to "civilize" Africa, the atrocities committed by some of the men packed on the raft of the Medusa were tarnishing French image even more :

-

No sooner had the raft lost contact with the other vessels than a spirit of

insurrection began to show, with screams of furore.

Ferocious looks were exchanged as if people were ready to devour each other and to feast on their neighbour's flesh. Some had already suggested recourse to this dire extremity, beginning with the fatter and the young. [...] Captain Dupont, banned from the raft because he refused to touch the sacrilegious meat on which the monsters were gorging themselves was miraculously saved from the hands of his executioners [...] The sixty survivors who escaped the first massacre on the raft were soon reduced to fifty, forty, then twentyeight [...] however the wine level was fast getting low and some of the leaders of the conspiracy were reluctant to halve the rations and eventually, in order to save them having to resort to this extreme measure, the executive committee found that it was wiser to drown thirteen people in order to have their wine rations than to halve the ration allocated to twentyeight. Good God ! What a disgrace ! (pp. 72-75)

Far from verifying the moral superiority claimed by France, this evidence of French people engaged in summary executions and cannibalism was shaking the very foundation of the whole colonial enterprise. It showed a reversal of the role; one incompatible with the civilising mission that the State promoted in order to justify its occupation of vast tracts of land. How could one justify that it was the very same people sent to Africa to impart a new sense of morality to the "natives" and to fight cannibalism who had engaged in random killings and eaten each other on their way to Senegal ? The only solution was to forget the whole sorry episode and to erase it from the collective memory in order to minimise its impact on the Nation. Paradoxically, Gericault's monumental painting of the raft of the Medusa facilitated this ploy. At first this canvas was seen as a controversial piece but it soon became a monument committed to the memory of a maritime tragedy cut loose from the unsavoury historical events that had inspired the artist in the first place[15].

Mme Dard's had a further reason to bother the government as her views on local African people and their relationship with European colonists were in complete contradiction to the colonial wisdom; one which took for granted that the "natives" lacked the faculty to think logically and were unable to experience life in the way any white persons would. In discrediting this falsehood that justified the horrors of the slave trade in previous centuries and soon became the main pillar of colonial exploitation, Mme Dard was giving the impression that she was again siding with the half-baked nonsense coming from London[16]. Furthermore, the open admission that her father was talking to his employees on equal terms and that he did not punish two slaves who attempted to run away looked like a reprehensible provocation :

-

"We like it here, one of them said, but we are not in our country; our parents

and friends are far away from us; our freedom has been taken away from us, thus

the attempt made and these we'll continue to make at the first opportunity to

recover it." He then added, addressing my father : " Yourself, Picard, my

master, if you were arrested when you are attending your fields and taken far

away from your family, wouldn't you do everything possible to go back to them,

to recover your freedom ?" My father who did not know exactly how to answer,

told him : "Yes, I would". "Nakamou ! (well !), retorted the negro, I am in a

similar case; like you I am the father a large family, I still have my mother,

uncles, a wife and children I love, so, why would you find it extraordinary

that I want to go back to them ?" (pp. 264-265)

Reasons to hush up Mme Dard's testimony were many and varied and one would be interested in knowing how the book was received upon publication, for instance in Dijon where it was published. Was it mentioned in Paris ? in Saint-Louis where the names of Picard and Dard were still fresh in everyone's memory ? And what about Jean Dard who opened the first French school in Black Africa in 1817 and married Charlotte Adélaïde Picard in 1820, just before returning to France, where, in 1826, he published a French-Wolof dictionary and a Wolof grammar[17] ? Was he victimised because of his wife's writing as would be the case years later for the family Bonnetain :

-

My husband would have been forgiven for his official reports that were duly

hushed up but I was not forgiven for the semblance of revelations contained in

my book. I was undiplomatically invited to the Chamber, but at the very time I

was awarded a purple ribbon, my husband was laid off. I do not think that my

latest scribbling offence can cause him trouble. [...]. Besides, how could he

be hassled as I'll stay clear of the forbidden paths and refrain from any

allusion to what I saw from the shady side of our colonial politics in Africa[18].

Future literary research will no doubt shed more light on Charlotte Adélaïde Dard's life and reveal the converging forces that combined to suppress her story[19]. What can already be said with certainty, however, is that the result expected by her detractors has, to date, been achieved : her writings have been conveniently lost for almost two centuries. As rightly argued by Mme Lapeyre, people's way of thinking is slow to change and the hierarchy governing gender's position "persists to this day"[20] yet, I believe that if Mme Dard's volume is still ignored in this day and age, it is not so much because it was written by a woman but rather because this woman was non-conformist and reflects unfavourably on the historical record that gave rise to our current beliefs, myths and values. Like Mme de Noirfontaine, Mme Bonnetain and many other writers, Mme Dard witnessed the messy days of early French colonial expansion, its viciousness, shambles and the untold damage to the world that continues to tarnish the Nation's image and its institutions' respectability. That, more than anything else, explains the reasons why her book is still largely being ignored by our contemporaries.

Jean-Marie Volet

2007

| Back to the main article : Women's perception of French colonial life in 19th century Africa, a fascinating universe challenging conventional wisdom |

Notes

[1] Her bibliography mentions 77 women travellers. Françoise Lapeyre. Le roman des voyageuses françaises (1800-1900). Paris : Payot, 2007, p. 10.

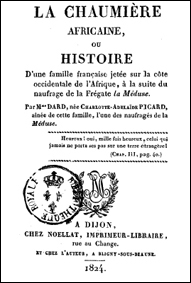

[2] Charlotte-Adélaïde Dard

(née Picard). La chaumière africaine ou Histoire d'une famille

française jetée sur la côte occidentale de l'Afrique,

à la suite du naufrage de la frégate la Méduse. Dijon

: Chez Noellat, 1824. Page numbers in the text refer to that book. All

translations are mine.

An English translation of Mme Dard's narrative by Patrick Maxwell (of Edinburgh) was included in Perils and Captivity, Edinburgh: Printed for Constable and co.

and Thomas Hurst and co. London, 1827. Available at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22792/22792-h/22792-h.htm Project Gutenberg EBook [Sighted 10 April 2008].

A section of Mme Dard's book was also published in English in "Shipwreck of

the Medusa on her voyage to Senegal, by Madame Dard" in The Mariner's

Chronicle : containing narratives of the most remarkable disasters at sea such

as shipwrecks, storms, fires and famines...". New Haven : R.M. Treadway,

1834, pp. 296-398.

[3] Lapeyre, p. 240.

[4] I cannot figure out why such an important narrative has escaped my attention for so long, especially as it was republished in 2005 in the collection « Autrement mêmes » with an Introduction by Doris Y. Kadish. Charlotte Dard. La chaumière africaine Ou Histoire d'une famille française jetée sur la côte occidentale de l'Afrique à la suite du naufrage de la frégate 'La Méduse'. Paris : L'Harmattan, 2005.

[5] Mme de Noirfontaine. Algérie, un regard écrit. Paris, 1856, p. 304.

[6] Lapeyre, p. 242.

[7] In the introduction to the 2005 re-edition of La chaumière africaine, Doris Kadish argues that the narrator's attempt to rehabilitate her father's reputation leads her to a simplistic dichotomy of good versus evil. In the end, Kadish suggests, the "so called persecutors" (p. xv) of the Picard family were nothing but new, enterprising colonists matched against an old and disgruntled competitor. In my view, this approach does not do justice to Mme Dard, her book and her father's character. M. Picard should not be dismissed in claiming casually that he was the "typical French whinger" (p. xii), a "good sort but far to eager in criticizing others" (p. xii) elevated to the standing of a "philosopher" by an "emotional and nostalgic" (p. xxx) daughter.

[8] A. Corréard and H. Savigny. Naufrage de la frégate la Méduse faisant partie de l'expédition du Sénégal en 1816. Paris : Chez Corréard, 1821, 5ème édition.

[9] J. B. Henry Savigny and Alexandre Corréard. Narrative of a voyage to Senegal in 1816 undertaken by order of the French government comprising an account of the shipwreck of the Medusa, the suffering of the crew, and the various occurrences on board the raft, in the desert of Zaara, at St. Louis and at the camp of Daccard . London : Henry Colburn, 1818, pp. 238-240.

[10] Gaspard-Théodore Mollien. "Le naufrage de la Méduse" in Découverte des Sources du Sénégal et de la Gambie en 1818. Paris : Delagrave, 1889, p. 31.

[11] Major Peddie refused to surrender his executive power to Colonel Schmaltz for months.

[12] Corréard et Savigny, p. 72

[13] According to Corréard et Savigny, p. 388. (Art.35).

[14] Corréard et Savigny p. 11.

[15] See http : //lettres.ac-rouen.fr/louvre/romanti/medus.html [sighted 18 August 2007]

[16] I do not share Doris Kadish's opinion when she mentions in the introduction of the 2005 re-edition of La chaumière africaine that Mme Dard « endeavours to depict an utopian view of White relationships with the Blacks » (p. xviii). I rather think that she held the same beliefs as her father and future husband Jean Dard in embracing the ideals of a French-African relationship wildly different from that which prevailed later. She anticipated a development of Saint-Louis based on freedom of the individual and solidarity between people : two virtues incompatible with a « French civilising mission », the main and only purpose of which was to pursue slavery under a different guise and to carry on with Africa's exploitation. There is nothing "utopian" in Mme Dard's exposition of race relationship. It is just an illustration of the human empathy and trust that was guiding the family's interrelations with "others".

[17] See http : //www.rfi.fr/Fichiers/MFI/Education/843.asp [sighted 18 August 2007]

[18] "La Femme aux colonies", Revue encyclopédique, 1896, cited in Lapeyre, p. 48

[19] Doris Y. Kadish provides preliminary information on these subjects in her introduction of the 2005 re-edition of the Chaumière africaine. Firstly, the section titled "Importance of the text" (p.xxxi) sketches an excellent analysis of the book's importance and reception by the critics. Secondly Kadish mentions useful documents offering new insight into Mme Dard's life and family. According to one of her sources, the Dard's family returned to Saint-Louis in 1832 where Mme Dard later become a teacher. Another source highlights the "heterogeneous nature" of the family as both her father and her husband had African women companions and the children born of these relationships were part of the family circle.

[20] Françoise Lapeyre notes that at the time she wrote her study, "the site Gallica of the French National Library, that listed one thousand five hundred and twentyfour entries on the theme of XIX century travel to Africa, only mentioned seven women travellers". Lapeyre, pp. 240-241.

Editor ([email protected])

The University of Western Australia/French

Created : 13 September 2007

Modifed: 10 April 2008

http : //aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/colonies_19e_eng.html