|

. |

Home Cet article en français Women in colonial times |

| Women's perception of French colonial life in 19th century Africa: |

| a fascinating universe challenging conventional wisdom |

A good number of people have written about Africa, yet important lacunas are still being exposed. The near absence of women writers from the colonial era is one of them. Few in number and marginalised in a corpus largely dominated by male writers, their voice is still to be heard. The recent literary success of many African women authors, early in the 21st century, should not distract us from the fact that little is known of the perception of Africa by women of previous generations.

A tentative exploration of the corpus led me to half a dozen books written by women - novels and travelogues - that reflect female experience of 19th century French colonial Africa[1]. Incomplete as it is, this sample opened the door to a fascinating literary universe that challenges official wisdom. More inclined to negotiation and dialogue, many women authors asserted a freedom of speech that was lost by male authors, "indebted and sworn actors whose inflexible position often contributed to biased judgments"[2].

Six letters published by Mme de Noirfontaine in 1858 under the title

Algérie un regard écrit [Algeria, a written outlook],

provide a compelling starting point to colonial writings. They illustrate that

women's views about French colonisation do not always concur with those of men

whose writings tend to overemphasise the themes of power, domination, conflict

and confrontation.

Six letters published by Mme de Noirfontaine in 1858 under the title

Algérie un regard écrit [Algeria, a written outlook],

provide a compelling starting point to colonial writings. They illustrate that

women's views about French colonisation do not always concur with those of men

whose writings tend to overemphasise the themes of power, domination, conflict

and confrontation.

Mme de Noirfontaine's experience of Africa dates back to the early years of French colonial expansion, barely 20 years after the first large scale French occupation of Algeria. The narrator does not tell us why, in 1849, she had to abandon Paris where she had lived "amongst sweet and glorious close friends" (p.5) and why she ended up "resettled in Africa at the stroke of a ministerial pen". (p.5) She was prepared for the worst but was, as she says, pleasantly surprised at discovering Algiers and later Oran, the city where she would spend the following three years. Her sojourn was highlighted by an endless string of encounters, discoveries, comments and observations. Blissful times alternated with dark moments and she shared both with friends who had remained in France.

Mme de Noirfontaine's empathy for her correspondents is the first element worthy of mention as it is indicative of the author's character and personality. Her only purpose in writing about her experience, she says in her preface, is not self-serving. It is "to entertain people I love"; hence the care she takes to avoid giving the impression that her presence in Africa and her close observation of colonial ways has led her to forget her friends' idiosyncratic beliefs and interests. She was clearly not interested in pushing her own story centre-stage if it meant losing the interest of her correspondents. She was anxious to share her ideas with others rather then telling them bluntly what she thought. Could it be argued that this preoccupation with others' expectations is a trait common to many women's approach to relationships? Not only do I believe that it is, but I think that it also influenced the themes captured in each letter and the way they were presented.

The third letter of the collection, addressed in November 1849 to Mme Julie Lallemand, strengthens this hypothesis. The whole letter deals with the cholera epidemic that, the narrator says, "pounced upon our poor city like a vulture and, as it were, froze my ability to speak, write and think !". (p.81) One may wonder why Mme de Noirfontaine gave so much importance to this dark episode of her life in this very letter. Is it because she is still suffering from the shock of seeing a large number of her friends and acquaintances dying ? Perhaps. But why tell it to Mme Lallemand rather than Mme Ancelot, the recipient of another letter on a different topic or any of the author's other friends ? A footnote brings us the answer to this interrogation: Mme Lallemand is the wife of Dr Lallemand, distinguished member of the French Institute. (p.83)

A letter dealing with the awful consequences of a plague that "mowed down one eighth of the population, a third of the garrison, seven doctors, 85 nurses and 12 Sisters from Saint-Vincent-de-Paul" (p.83) was obviously of interest to the family of a renowned doctor, "who was to the medical profession what Louis the XIV was to royalty". (pp.81-82) This letter is also interesting to a contemporary reader as it is reminiscent of a page written by Albert Londres in his celebrated Terre d'ébène (published in 1929)[3] and invites a comparison. Upon arriving in sight of Dakar, "the city of the Devil", right in the midst of a yellow fever epidemic, Londres noted: "For the second time, I could not reach Dakar. It was out of bounds. Dakar was plague-stricken. Ships were fleeing as fast as they could [...] The nightmare lasted five months. One point five deaths every day ! The women and children had gone. Only men remained, according to the rules !". (pp.14-15)

Regardless of one's opinion of Londres[4], one cannot but note that he has little sympathy for a nasty place, one inhabited mainly by men deprived of their women and children and where the Senegalese women who lived there were just ignored. Mme de Noirfontaine's depiction of colonial Africa contrasts sharply with Londres' dismal and macho rendition. Welcoming diversity and multiplicity in terms of race and gender, she includes both women and the local population who were all in the same boat when the epidemic struck. She takes an interest in the Moorish women confined behind the high walls of family dwellings (First letter addressed to M. Léon Gozlan), on the lives of Bedouin women overburdened by domestic chores (Fifth letter addressed to Mme. Daullé), but also to political and religious elders who lead her to discover a rich and complex culture that endured many conquests and survived "thirteen centuries of trials and tribulations". (p.257) Thus, Mme de Noirfontaine's conclusion in her letter to Eugène Chapus, "The Arabs do not see what they would gain in adopting our way of life".

-

Is that sufficient to conclude that the Arab race is inferior to our own ? No !

But that it is a different race which has other needs, other instincts,

other ways, one that is also conditioned by physical attributes and the climate

: in a word, the milieu where they live. If one pushes aside the prejudicial

feelings inherited from habit or spite, one has to admit that the Arabs, like

everybody else, are neither entirely good nor entirely bad and that human

nature which is evil everywhere, is no more vicious in Algeria than in

civilised countries where serious disturbances and dreadful crimes are being

committed in spite of pervading intelligence and instruction. (pp.288-289)

Twenty years after the French occupation of Algeria, Mme de Noirfontaine is one of the first persons to articulate the hypocrisy of the colonial conquest which is going to spread southward in the name of "civilizing missions", elevated to the status of a National duty. The ad hoc political decisions and mercantile preoccupations that were behind French expansion did not escape Mme de Noirfontaine either. She mentioned them in her letter to Mme Daullé: "You will no doubt remember in what circumstances our colonies were set up ? The idea was to put back to work thousands of hands left idle in the streets of Paris; the farming colonies were the only expedient one could find to answer the crisis of the day". (p.208) Moreover, her letter to Eugène Chapus adds:

-

When we embarked on the conquest of Algeria, we did not do so as a religious

people harbouring passionate feelings under the guise of political coldness. We

set about settling the country ... as business people who only have material

gains in sight and only measure the usefulness of action in term of its

results. No matter how one cares to spin out the facts, it is obvious that in

the final analysis, our Generals - some of whom have proven to be among the

best in the world - have only fought a splendid industrial campaign.

(p.280)

There is something surprisingly modern in this analysis that expresses quite well the current ill of military interventions which are at the heart of economic expansion, yet call upon people's freedom and democratic values to justify their actions. Mme de Noirfontaine was touching a raw nerve at the time and still does, more than a century later, as the unholy alliance of politics and big business continues to hold sway, supported by powerful armies and their decorated generals. No surprise then that French history never did do justice to her work and that current scholarship on the other side of the world never came to her rescue: in the name of State security, one might say. The logical answers to the questions she was asking could do nothing but embarrass the "elite circle" (p.171) boasting of the Empire's success and strutting at the top of the socio-economic order.

However, she suggested that dodging important issues and fooling the Nation could only lead to the tragic ending of this ill-conceived adventure; and we are still being affected by its disastrous consequences today. From the start, colonialism was doomed because it was exploitative rather than collaborative in nature:

-

Let me put to you an hypothesis, possibly bizarre but calculated to explain my

thoughts, going straight to the point. Let's assume, for argument's sake, that

against all odds we succeed in making Algeria a subsidiary of France, that we

eventually manage to acculturate the Arabs to our habits, our fashion and our

tastes. Do you think they will be better dressed once they have swapped their

classic burnous for our romantic overcoats, their poetic turbans against our

prosaic caps ? Will they be happier when, instead of cultivating their fields

and living peacefully on the returns from their land, they will have embraced

our costly extravagances, stimulated by an ambition well beyond their resources

?

Will they be more honourable, when, instead of listening to the poets and storytellers of Arabia, they engage in codified writing and literary acrobatics of a journal bending with the wind, sometimes white, sometimes red, sometimes blue ? when they follow the incredible u-turns and vagaries of the critique which is quick to hate today what was loved yesterday, to blame at dusk what was approved of at dawn, bearing witness to all things except sincerity ? Eventually, will they be more moral, better equipped to rise to heaven when, instead of celebrating the glory of God under the dome of their mosques, they will debate publicly the immortality of the soul in clubs, or sing bacchanalian tunes in orgiastic taverns ?

Being only a simple women who knows nothing, understands little and thinks even less, I leave it to the authoritative reformers who are more clever than I, to give the appropriate answer to such important questions. (pp.302-304)

It is easy to guess that the imperial administration did not want to hear such kind of reasoning and took the necessary steps in order to make sure it would not spread. Thus my suspicion of the prompt disappearance of the book to the remotest corner of the Imperial Library where it remained buried for almost two centuries. Not an unusual event, one may say, as many authors have suffered the same fate. However, the cost of this disappearing act was to deprive France of a unique analysis of the colonial pitfalls, one that held the key to a better understanding of the Arab and African worlds: two topics that are still as widely misunderstood in France in 2007, after more than one century of French occupation, as they were in 1849.

The reasons for French colonialism's failure are difficult to grasp on the basis of the self-serving discourse of officialdom. They are much easier to explain using Mme de Noirfontaine's assessment. She highlights, for example, the deficiency of Paris' political elites and their narrow understanding of the issues that became so catastrophic. Prone to sneer at women when they dared to disagree and expressed a differing opinion, the specialists were more readily swayed by fashionable writers - such as newspaper columnist and novelist Eugène Chapus who, as Mme de Noirfontaine puts it, in teasing him, "managed to give to their dreams the appearance of the truth". Writers endowed with a vivid imagination, wrote books about a continent on which they had never set foot and had only seen while seated next to the mantle piece of their dining room. (pp.252-253) The future of Africa, Mme de Noirfontaine said, is decided in administrations and by people who know little of it and whose main purpose is to exploit the place in any way they can.

In this context, the wild fabrication put forward by Jules Verne in Five weeks on a balloon (published in 1863) is one of the most notorious examples. This book brought financial security to its then fledgling author and influenced dramatically perceptions of Africa throughout the 19th and 20th Centuries. The fanciful ideas dreamed up by this generation of authors were perpetuated by following generations, even to this day. Some women writers, it is true to say, also added their pens to airing that hackneyed and distorted vision of the continent and its inhabitants. Perdue en Afrique [Lost in Africa] by Mme L.G. Renard (published in 1926) is a case in point. Sojourning in Africa, however did not necessarily imply an intimate knowledge of the continent, nor did it vouch for the sincerity of the writers[5]. Some were trying to show off, some to please an influential personality or a powerful sponsor and some were:

-

inflicting unmercifully upon their readers the most trivial of comments; having

crossed a country during the night and seen it half-asleep, eyes

half-shut, they felt compelled to tell how the place looks to a traveller who

had fallen asleep. (p.180)

Another contributor to colonial failure, Mme de Noirfontaine suggests, is gender divergent attitudes to violence. Men and women do not have similar views on wars, national honour and military successes, she said in a letter addressed to Colonel Marnier. Furthermore, the overbearing influence of "masculine" approaches in conflict resolution goes hand in hand with undesirable consequences:

-

The more I was listening to him, she said, all these atrocities struck me and

I was under the impression that I could see these wild beheaders rushing

indiscriminately towards their brothers and ours, that I could hear the

salvoes, the raucous noise of the victors and the death-rattle of the dying [...]

Then thoughts about families began to enter my mind; I was thinking of the poor

mothers, the poor women with bleeding hearts who suffer so much during wars. -

How many fears ! How much anguish ! How many blurred and horrible visions

come to beset them ! Men knock themselves into a daze in the melee; they roll

about in an incendiary swirl fuelled by their power and hatred, all senses

inflamed by a fervour burning like larva in their veins, leaving no time for

their mind to think and ponder, whereas the poor women ... neither dazzled by

fame nor inebriated by ambition, remain unprotected, bereft of any shield and,

the shot that hits them they receive in the dark, motionless, speechless and

powerless to defend themselves or to take revenge. [...] When men carry hell

and destruction in their minds, it is to no purpose that Providence offers them a

haven leading to love and peace as they refuse to associate themselves with

harmony, brushing its appeal aside in order to indulge in self-inflicted pain.

(pp.73-74)

Whereas men crave the opportunity to show their bravery and to distinguish themselves by engaging in feats of arms, followed by death, devastation and hate, women, unmoved by military honours, long for peace and reconciliation as they are, more often then not, the main casualties of war. Each and every military victory bears the seed of a forthcoming defeat if the main reasons behind a confrontation have been left unresolved and the fighting parties remain well apart on "the form and the substance"[6]. (p.314)

Gender specific ways of behaving, thinking and writing should not be overstated, yet a major imbalance between the importance given to male writings compared to that of women explains, at least in part, the uni-dimensional (and unsuitable) image of Africa that has been popularised to this day. Moreover, as the prerogative to write the country's history and to bestow honours has been overwhelmingly male dominated until very recently, it is easy to understand why national psyche has favoured a manly approach in its depiction of the past: Widows, orphans, as well as the mercenary "chaouchs [...] who were given the responsibility to uphold a system of healthy lashings under the benevolent yoke of our domination" (p.184) have been erased from the picture and replaced by Napoleon III's enduring slogan: "Empire means peace !". This falsehood, expressed by a man who was not averse to contradicting himself, was perpetuated over the centuries against a background of military operations, people's oppression and bloody battles.

Mme de Noirfontaine offers a take on colonial expansion which opposes the view of many experts, but it does not prove a priori that her preoccupation with alterity expresses sentiments commonly held by other women writers of her time. Furthermore, one may argue that her exclusion from history is coincidental rather than typical of the hand dealt to women by recorded history. However, a tentative investigation of titles published by women around the same time seems to suggest otherwise.

Mme de Noirfontaine's keen interest in women's condition and women's issues is

the first topic that can be found, in varying degrees, across all the books at

hand. It is interesting, for example, to note that almost two centuries before

the publication of Reines d'Afrique [Queens of Africa][7] by

Sylvia Serbin (in 2004), Mme d'Abrantès had already published a book

titled Les femmes célèbres de tous les pays, leurs vies et

leurs portraits[8] [Famous women from

all countries, their lives and portraits] in which she told, among others, the

life-story of Queen Zingha, Queen of Matamba and Angola.[9] Mme d'Abrantès never rose to literary fame, but it

was not for lack of the numerous, interesting books that survive her. A friend

of the Bonaparte family, she was also a leader of society and had much to say

about 19th century life from a female point of view. I would argue

that it is not by accident that she took an interest in famous women and their

deeds. It is rather consistent with a kind of common interest by

women in other women's lives and conditions[10]. Nor is it on the basis of well defined criteria that her

writing was omitted from canonic work.

Mme de Noirfontaine's keen interest in women's condition and women's issues is

the first topic that can be found, in varying degrees, across all the books at

hand. It is interesting, for example, to note that almost two centuries before

the publication of Reines d'Afrique [Queens of Africa][7] by

Sylvia Serbin (in 2004), Mme d'Abrantès had already published a book

titled Les femmes célèbres de tous les pays, leurs vies et

leurs portraits[8] [Famous women from

all countries, their lives and portraits] in which she told, among others, the

life-story of Queen Zingha, Queen of Matamba and Angola.[9] Mme d'Abrantès never rose to literary fame, but it

was not for lack of the numerous, interesting books that survive her. A friend

of the Bonaparte family, she was also a leader of society and had much to say

about 19th century life from a female point of view. I would argue

that it is not by accident that she took an interest in famous women and their

deeds. It is rather consistent with a kind of common interest by

women in other women's lives and conditions[10]. Nor is it on the basis of well defined criteria that her

writing was omitted from canonic work.

Ida Pfeiffer's meeting with Queen Ranavalo in Antanarivo in 1857 provides

another example. In her Voyage à Madagascar [Travel to

Madagascar][11], Mme Pfeiffer gives her

impressions from the vantage point of a European woman; one who is welcomed as

such by another woman, the proud and all-powerful Queen of Madagascar. The

latter asked her visitor to play the piano, and the former takes an interest in

issues most men would have ignored. For instance, her scrutiny and thorough

description of Court's fashion is but one example among many:

Ida Pfeiffer's meeting with Queen Ranavalo in Antanarivo in 1857 provides

another example. In her Voyage à Madagascar [Travel to

Madagascar][11], Mme Pfeiffer gives her

impressions from the vantage point of a European woman; one who is welcomed as

such by another woman, the proud and all-powerful Queen of Madagascar. The

latter asked her visitor to play the piano, and the former takes an interest in

issues most men would have ignored. For instance, her scrutiny and thorough

description of Court's fashion is but one example among many:

-

I will describe one of these costumes so that my women readers can have an idea

of how they look. The dress was made of velvet of blue silk, lined at the

bottom with an orange edging topped by a wide stripe of cherry-red satin. The

bodice, with long tails, made of satin as well, was of a vivid sulfur-yellow

[...]. (p.231)

When the author was writing these lines, she was undeniably doing so from the viewpoint of a woman who had other women in mind. Thus one of the feature of this travelogue is that it does not limit itself to women's issues, but acknowledges their existence. The story of a powerful Queen who managed to repel French colonial armies and that of an elderly women traveller heading for Madagascar on her own both provide evidence of the fact that, contrary to common belief, male protagonists were not the only recorders of historical development. Allowing women's experience to be sidelined can only lead to a distorted expression of historical truth.

The novel Ourika, published in 1823 by Mme de Duras is yet another

testimony to women authors' interest in women's issues. Ourika draws its

plot from the true story of a little Senegalese girl torn from her native land

and presented, as a gift, to Mme de Beauvau by her nephew, The Chevalier de

Boufflers, Governor of the newly established colony of Senegal. Upon its

publication, Mme de Duras' novel became very popular. It was translated into

Spanish and English, and reprinted many times during the author's life.[12] However, this success was not sufficient to

sustain this delightful novel as a fine

specimen of literary achievement beyond the 19th century. Adding insult to injury, the survival of Mme

de Duras' name in literary circles was not associated with her literary

achievements, but to the fact that she had been a very good friend of

Chateaubriand. A great many women authors and publications have known the same

fate and one would be hard-pressed to find, in the French literay canon, any

text dealing with colonial alterity written by a female author. Not that these

texts do not exist. They have just been overlooked.

The novel Ourika, published in 1823 by Mme de Duras is yet another

testimony to women authors' interest in women's issues. Ourika draws its

plot from the true story of a little Senegalese girl torn from her native land

and presented, as a gift, to Mme de Beauvau by her nephew, The Chevalier de

Boufflers, Governor of the newly established colony of Senegal. Upon its

publication, Mme de Duras' novel became very popular. It was translated into

Spanish and English, and reprinted many times during the author's life.[12] However, this success was not sufficient to

sustain this delightful novel as a fine

specimen of literary achievement beyond the 19th century. Adding insult to injury, the survival of Mme

de Duras' name in literary circles was not associated with her literary

achievements, but to the fact that she had been a very good friend of

Chateaubriand. A great many women authors and publications have known the same

fate and one would be hard-pressed to find, in the French literay canon, any

text dealing with colonial alterity written by a female author. Not that these

texts do not exist. They have just been overlooked.

The ability to understand and share the preoccupations of someone else is also noticeable in 19th century women authors' opposition to the slave trade. Like the French colonisation of Algeria, the initial emancipation of French slaves in 1793-1794 was a political expedient rather then the result of humanitarian preoccupations. Its purpose was to weaken the white loyalists of Saint-Domingue and to defuse Spain's and England's military threat[13]: thus the restoration of slavery by France in 1802, as soon as those threats faded away. Die-hard attitudes led to a prolongation of slavery by fifty years as socio-economic considerations were paramount despite an overwhelming opposition to slave trading in many parts of Europe and in France itself.

Numerous writers agitated against this inhumane exploitation of African labour.

Among them Mme Doin who published a number of books condemning the evil of

slavery and its undesired effects on women, children and families. Her novel,

La famille noire [The Black family][14], recently recovered from the abyss, denounces "the

unprecedented misfortune which, for many centuries, has oppressed forlorn

Africans". (p.5) This short novel is testimony to the author's care for the

plight of others, in spite of her own personal drama that put her at the mercy

of an extravagant husband. Like the characters of her novel, she displayed

"courage, resolution and both moral and physical strength"[15]. However this kind of strength that relates to concrete

interpersonal relationships was outside the "higher order" preoccupations

jealously guarded by the leading thinkers of her time. Consequently, the voices

of those women who fought so vigorously to change the world, without spiling

blood, were lost in the anonymity of unsung activities that faded with time.

Numerous writers agitated against this inhumane exploitation of African labour.

Among them Mme Doin who published a number of books condemning the evil of

slavery and its undesired effects on women, children and families. Her novel,

La famille noire [The Black family][14], recently recovered from the abyss, denounces "the

unprecedented misfortune which, for many centuries, has oppressed forlorn

Africans". (p.5) This short novel is testimony to the author's care for the

plight of others, in spite of her own personal drama that put her at the mercy

of an extravagant husband. Like the characters of her novel, she displayed

"courage, resolution and both moral and physical strength"[15]. However this kind of strength that relates to concrete

interpersonal relationships was outside the "higher order" preoccupations

jealously guarded by the leading thinkers of her time. Consequently, the voices

of those women who fought so vigorously to change the world, without spiling

blood, were lost in the anonymity of unsung activities that faded with time.

This subservient role of women's activities oftentimes mirrors women writers'

relationships with their family, their milieu and the world at large. A reason

is always found to devalue their observations and to find them "of little

relevance as it is well-known that women never move beyond the superficial

aspect of things", as Mme de Noirfontaine wrote in the preface of her book.

Added to that, men of influence were eager to protect their prerogatives. Mme

Bonnetain's travelogue Une Française au Soudan [A French woman in

Sudan][16] is interesting in this regard. The

beginning of the book deals with her efforts to convince her husband, and then

the Ministry, that she was fit to travel to Africa. She needed a fierce

determination to challenge common practice and her departure for Sudan in 1892

is strongly resisted by all. As outlined by Albert Londres in Terre

d'ébène, " The hut in the bush, the conquest of the black

soul and the little Mousso" were men's business[17] and Paul Bonnetain "was dying to embark for Africa".

(p.2) "I could see it", his wife wrote, so:

This subservient role of women's activities oftentimes mirrors women writers'

relationships with their family, their milieu and the world at large. A reason

is always found to devalue their observations and to find them "of little

relevance as it is well-known that women never move beyond the superficial

aspect of things", as Mme de Noirfontaine wrote in the preface of her book.

Added to that, men of influence were eager to protect their prerogatives. Mme

Bonnetain's travelogue Une Française au Soudan [A French woman in

Sudan][16] is interesting in this regard. The

beginning of the book deals with her efforts to convince her husband, and then

the Ministry, that she was fit to travel to Africa. She needed a fierce

determination to challenge common practice and her departure for Sudan in 1892

is strongly resisted by all. As outlined by Albert Londres in Terre

d'ébène, " The hut in the bush, the conquest of the black

soul and the little Mousso" were men's business[17] and Paul Bonnetain "was dying to embark for Africa".

(p.2) "I could see it", his wife wrote, so:

Mme Bonnetain's decision to travel with her seven year old daughter further inflamed the situation. If her duty was to follow her husband, it was also to wait for him at home with her daughter. And it was up to him to decide which one of these two obligations that contradicted one another would be the most suitable. But Mme Bonnetain would hear nothing of it and in due course embarked semi-clandestinely. Her husband, she says, "did not dare to say I was travelling with him - at least did not declare it officially" (p.90) and he paid his wife and daughter's passage with his own money.

-

It would have been necessary to set a precedent for us, Mme Bonnetain

says, and you wont need a picture, dear Claire, and you, Suzanne, and also you

Jeanette, who are all the very ordered wives of military men and civil

servants, to understand the magnitude of the issue. (p.90)

Mme Bonnetain's arrival in Africa was therefore greeted with suspicion and resentment in maritime and military circles, thus the telegram addressed to M. Bonnetain by a local Colonel who leaves no doubt about his feelings: "Sudan is no place for distinguished women". (p.90) Mme Bonnetain and her daughter's subsquent travel through a region "that was not meant for them" resulted in a 378 page travelogue: an important volume to bring to the fore, even if only because it provides a distinct view of early French colonial days.

Missionaries' approach to the continent was somewhat different from that of

military personnel and civil servants. From the beginnings of the continent's

evangelisation, the missions welcomed, more readily, women in remote areas.

Nevertheless, all colonial institutions concurred in their attitudes to women

and only offered them very limited opportunities to act independently. Rigid

hierarchies made it difficult to escape subservience to men who were taking

ultimate responsibility for their womenfolk's actions[18], thus failing to acknowledge the true extent of their

work. Mme Schrumpf's life told by the author in her Autobiography[19] is characteristic of these constraints. Born

in 1815 in Prussia, she became a private tutor and a teacher in Switzerland and

later France when she had a calling to become a missionary. That proved

impossible to pursue in the first instance as the French Evangelical Mission

refused to send a free-spirited and unattached woman to Africa. Thus her

marriage of convenience in 1842, to Preacher Jean-Christian Schrumpf who was

heading to Southern Africa. Subsequently, she stayed sixteen years in remote

parts of the continent and her living conditions were extremely harsh. She had

to negotiate her way through a succession of droughts and floods, food

shortages, pregnancies, miscarriages and major illnesses that nearly killed her

husband and sent one of her children to the grave. In reading Mme Schrumpf's

autobiography, one soon realises that she was the driving force behind her

family's survival, providing her husband with the resources he needed to go

about his "high order" assignment of "destroying the stronghold of paganism"

and "saving pagan souls". A despondent M. Schrumpf failed to convert as many

people he and his superiors in Europe had hoped for. That led him to suffer

from depression which added to his wife's precarious situation. Yet her stamina

and personal achievements were lost in the Mission's Head Office's appraisal of

the Schrumpf family performance which was considered as modest. M. Schrumpf's

persona rather than Mme Schrumpf spirited commitment was used as the measuring

rod. Thus the lack of specific reference to her work in Théophile

Jousse's Histoire de la mission française

évangélique [History of the French Evangelical Mission],

published in 1889[20]. M. Schrumpf is

remembered in a few ambivalent paragraphs but she is mentioned only once, and

then in the shadow of her husband: "it has not been lost that it was M.

Schrumpf and his faithful companion who first brought the word of God to the

Bapoutis of the Maphoustsing". (p.375)

Missionaries' approach to the continent was somewhat different from that of

military personnel and civil servants. From the beginnings of the continent's

evangelisation, the missions welcomed, more readily, women in remote areas.

Nevertheless, all colonial institutions concurred in their attitudes to women

and only offered them very limited opportunities to act independently. Rigid

hierarchies made it difficult to escape subservience to men who were taking

ultimate responsibility for their womenfolk's actions[18], thus failing to acknowledge the true extent of their

work. Mme Schrumpf's life told by the author in her Autobiography[19] is characteristic of these constraints. Born

in 1815 in Prussia, she became a private tutor and a teacher in Switzerland and

later France when she had a calling to become a missionary. That proved

impossible to pursue in the first instance as the French Evangelical Mission

refused to send a free-spirited and unattached woman to Africa. Thus her

marriage of convenience in 1842, to Preacher Jean-Christian Schrumpf who was

heading to Southern Africa. Subsequently, she stayed sixteen years in remote

parts of the continent and her living conditions were extremely harsh. She had

to negotiate her way through a succession of droughts and floods, food

shortages, pregnancies, miscarriages and major illnesses that nearly killed her

husband and sent one of her children to the grave. In reading Mme Schrumpf's

autobiography, one soon realises that she was the driving force behind her

family's survival, providing her husband with the resources he needed to go

about his "high order" assignment of "destroying the stronghold of paganism"

and "saving pagan souls". A despondent M. Schrumpf failed to convert as many

people he and his superiors in Europe had hoped for. That led him to suffer

from depression which added to his wife's precarious situation. Yet her stamina

and personal achievements were lost in the Mission's Head Office's appraisal of

the Schrumpf family performance which was considered as modest. M. Schrumpf's

persona rather than Mme Schrumpf spirited commitment was used as the measuring

rod. Thus the lack of specific reference to her work in Théophile

Jousse's Histoire de la mission française

évangélique [History of the French Evangelical Mission],

published in 1889[20]. M. Schrumpf is

remembered in a few ambivalent paragraphs but she is mentioned only once, and

then in the shadow of her husband: "it has not been lost that it was M.

Schrumpf and his faithful companion who first brought the word of God to the

Bapoutis of the Maphoustsing". (p.375)

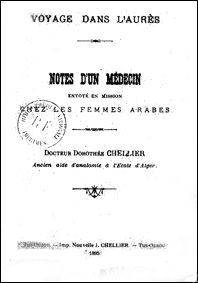

The North-Africans met by Mme de Noirfontaine did not need the French to run

their lives; the Southern-Africans approached by M. Schrumpf did not need his

religion to cleanse their soul. Strong-arm tactics and intolerance do not work

in the long run and better alternative strategies could be developed. That is

the message that comes loud and clear from the various authors mentioned above.

That is also the view of Dr Chellier with regard to heath issues.

Dorothée Chellier was one of the first French doctors who, incidentally,

hailed from Algeria. She conducted a health mission in the Aures region in

1895, and came to the conclusion that:

The North-Africans met by Mme de Noirfontaine did not need the French to run

their lives; the Southern-Africans approached by M. Schrumpf did not need his

religion to cleanse their soul. Strong-arm tactics and intolerance do not work

in the long run and better alternative strategies could be developed. That is

the message that comes loud and clear from the various authors mentioned above.

That is also the view of Dr Chellier with regard to heath issues.

Dorothée Chellier was one of the first French doctors who, incidentally,

hailed from Algeria. She conducted a health mission in the Aures region in

1895, and came to the conclusion that:

In her Notes d'un médecin envoyé en mission chez les femmes arabes [Notes from a doctor sent on a mission among Arab women][21], she wrote:

I also wondered whether a woman doctor could do something useful in introducing our ideas in an environment so stubbornly and deliberately apart from our own.

[...]

Knowing all these things and keen to complete the observations I had already made on the natives' customs, I requested from the Governor General that he be kind enough to entrust me with a mission to a remote location [...] M. Cambon [...] suggested a study of childbirth, miscarriage and uterine diseases in the Aures mountains. (pp.5-6)

And a few lines down:

-

It is always by acting upon the women's mind that one can really reach the

whole family. Attempting to make a direct impression on an adult male almost

always amounts to an irrational endeavour with no practical results. [...] the

new medical profession should not be comprised only of men. (p.7)

These short extracts from an outspoken Dr Chellier underline the same strength of character and common-sense as those shown by Mme de Noirfontaine fifty years earlier. They testify to a thorough understanding of the colonial milieu, analytical skills that go to the root cause of the issues, a recognition of the importance of women's role in history, a marked interest in women's issues regardless of race and colour. Losing sight of the real word, colonial literature and history have engaged in the pursuit of their own finality; women's writing has been brushed aside in spite of the fact that often:

-

When rich, women are in command and rule; when poor, they work and their lazy husbands

sleep, drink and eat unless a war comes along, awakening their bellicose

instincts; then they fight like lions. But women are every bit as good as them

when it comes to bravery and courage.[22]

Summoning long time absentee authors provides an opportunity to cross-examine conventional wisdom and to show that there are always alternatives to violent struggles and bloody "pacifying" missions. Alternatives that are still relevant today.

Jean-Marie Volet

2007

| ADDENDUM : Mme Dard, the shipwreck of the Medusa in 1816 and the early colonisation of Senegal |

Notes

[1] An introduction to 19th century writings in French by women can be found in Béatrice Slama "Un chantier est ouvert... Notes sur un inventaire des textes de femmes du XIXe siècle". Romantisme 77-3, 1992, pp.87-94, suivi de "Pour une bibliographie des récits de voyages au féminin (XIXe siècle)" de Bénédicte Monicat, pp.95-100.

[2] Mme de Noirefontaine. Algérie, un

regard écrit. Paris. 1856. Préface. Quotes are translated

from French original.

Another extract from Les mystères de l'Egypte dévoilés

by Mme Olympe Audouard [Paris: E. Dentu, 1865, p.3], highlights that

dependence on political correctness: "The articles published in newspapers in

Paris or elsewhere are written by people who live in Egypt and who are not paid to

speak ill of the government ... The local newspapers, i.e., those that dare to

say that things are not happening in the best possible world are promptly

terminated... As far as the newspaper L'Egypte is concerned, it is

different still: as it belongs to the Vice-King, the latter cannot really

afford to spend one hundred thousand francs a year on this publication in order

to criticise his own way of governing the country... it would be just too

silly...".

[3] Albert Londres. Terre d'ébène. (1929) Paris: Le Serpent à Plumes, 1998.

[4] who has been rightly praised for his critique of human exploitation in the French colonies

[5] Mme Audouard wrote in her book on Egypt: "I know some Europeans who spent thirty years in Egypt and did not even pay a visit to the Pyramids; the only places they know of in this country are the markets, the club, the hotel and the waiting room of the Viceroy. Should you mention common practice, the Copts or the customs of the Arab peasants, they would know absolutely nothing on the subject and answer: "Pooh ! what is it to us...? We are not here to waste time taking care of these people, we are here to make money..." Mme Olympe Audouard. Les mystères de l'Egypte dévoilés, 1865, p.3.

[6] That was intuitively understood by the young Lucie Felix-Faure - whose father became French President in later years - when she travelled with him to Algeria and Tunisia: "Possibly the best welcome from the natives we received was in the Holy City. As Kairouan had surrendered uncondionally, we had the right to visit all the mosques: something strictly forbidden in Tunis. But is it really generous of us to repay the Arabs' trust in exercising this right ?" Felix-Faure. Une excursion en Afrique. Paris: Ludovic Baschet, 1888, p.91.

[7] Sylvia Serbin. Reines d'Afrique et héroïnes de la dispora noire. Saint-Maur-des-Fossés: Sépia, 2004.

[8] Duchesse d'Abrantès. Les femmes célèbres de tous les pays, leurs vies et leurs portraits. [Zingha, reine de Matamba et d'Angola], Paris: Librairie de la Polonaise, 1835, pp.7-25.

[9] Queen Zingha, a shrewd negotiator, managed to keep the Portuguese invaders at bay throughout the 17th century and foil many attempts to conquer her kingdom. As far as Mme D'Abrantès is concerned, on top of her 18 volumes of Memoirs, she published numerous titles dealing with her travels around Europe in the 18th century, the Paris salons, etc.

[10] Lucie Felix-Faure's sojourn in Algeria and Tunisia illustrates this interest in women living conditions, fashion, activities... Her travelogue shows the narrator's inclination for keen observation. One example, p.10.: as she sat at the window in order to look at passers-by, it is mainly women who attract her attention, thus the description of various women clothes". Lucie Felix-Faure. Une excursion en Afrique. 1888.

[11] Ida Pfeiffer. Voyage à Madagascar. Paris: Librairie L. Hachette, 1862, 312p. Translated from German.

[12] Christiane Chaulet Achour. "Préface" in Madame de Duras. Ourika. [1823]. Saint-Pourçain-sur-Sioule: Bleu autour, 2006, p.13.

[13] Doris Y. Kadish. "Introduction" in Sophie Doin, La famille noire suivie de trois nouvelles blanches et noires. [1825]. Paris: L'Harmattan, 2002, p.xv.

[14] Sophie Doin. La famille noire suivie de trois nouvelles blanches et noires. [1825]. Paris: L'Harmattan, 2002. [Introduction de Doris Y. Kadish].

[15] Y. Kadish. Op.cit., p. xxiii.

[16] Mme Paul Bonnetain. Une Française au Soudan. Paris: Librairies-Imprimeries Réunies, 1894, 378p. [Reedition in the collection Autrement Mêmes : Raymonde Bonnetain, Une Française au Soudan : sur la route de Tombouctou, du Sénégal au Niger, Paris: L'Harmattan, 2007. Presentation by Jean-Marie Seillan].

[17] Londres, Op. cit., p.17

[18] Monseigneur Augouard's authoritarian attitude toward Mother-Superior Marie-Michelle Dédié - who was sent to Congo by her Order in 1893 - provides a good example. Phillis M. Martin. "Celebrating the Ordinary: Church, Empire and Gender in the Life of Mère Marie-Michelle Dédié (Senegal, Congo, 1882-1931)", Gender & History, Vol.16, No2, 2004, pp.289-317.

[19] Mme Rosette Schrumpf. Autobiographie de Mme Rosette Schrumpf née Vorster, missionnaire au sud de l'Afrique. Strasbourg: C. Schrumpf, 1863. 100p.

[20] Théophile Jousse. La mission française évangélique au sud de l'Afrique, son origine et son développement. Paris, 1889, (vol.2, p.345).

[21] Docteur Dorothée Chellier, Ancien aide d'anatomie à l'école d'Alger. Notes d'un médecin envoyé en mission chez les femmes arabes. Tizi-Ouzou, Imprimerie Nouvelle, 1895.

[22] Madame de Voisins. Excursions d'une Française dans la régence de Tunis. Paris: Maurice Dreyfous, 1884, p.262.

Editor ([email protected])

The University of Western Australia/French

Created: 31 May 2007

Modified: 13 dec 2007

https://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/colonies_19e_eng.html