|

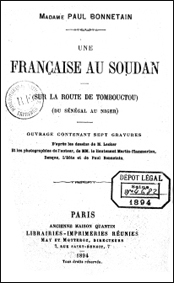

NOT TO BE MISSED "Une Française au Soudan. Sur la route de Tombouctou, du Sénégal au Niger" [A French Woman in Sudan: On the road to Timbuktu, from Senegal to Niger], a travelogue by Madame (Raymonde) BONNETAIN Paris: Librairies-Imprimeries réunies, 1894. (378p.). Reprint by the Editions l'Harmattan in 2007

|

Ce compte rendu en français |

When the seasoned colonial writer and journalist Paul Bonnetain was sent on assignment to Sudan by the French Government, his young wife faced a barrage of opposition when she decided to follow her husband to Africa, together with her daughter and her dog. As the Colonel Archinard, Head of operations in Sudan told Bonnetain by telegram: "Sudan unsuitable for women about town" (p.93). But twenty-four year old Raymonde was not to take "No" for an answer. "Some families adapt to living apart", she says. "Not us" (p.3). Determined to "extract her husband's consent" (p.17), she embarked aboard the Portugal in November 1892, reaching Senegal eight days later. Une Française au Soudan details the family's long trek from Dakar to Sudan and Niger.

From a literary point of view, this travelogue, initially written for family and friends, is an unassuming diary rather then a trailblazing narrative. But Raymonde Bonnetain's rendition of colonial life and her candid criticism of colonial inefficiencies are interesting because they reflect common perceptions in late 19th century France. The crude exploitation of Black labour condoned by slavery was out of fashion, and opening Africa to the world was the order of the day. Unlike her grandparents who owned slaves in Brazil many years earlier and vigorously protested the abolition of slavery, Raymonde Bonnetain was part of a generation with different concerns. "What shocked our beliefs and philosophical ideals, she says, was to see Whites buying, owning and selling Blacks" (p.68). Now was the time to bring French civilisation to the slaves who had been set free.

From a literary point of view, this travelogue, initially written for family and friends, is an unassuming diary rather then a trailblazing narrative. But Raymonde Bonnetain's rendition of colonial life and her candid criticism of colonial inefficiencies are interesting because they reflect common perceptions in late 19th century France. The crude exploitation of Black labour condoned by slavery was out of fashion, and opening Africa to the world was the order of the day. Unlike her grandparents who owned slaves in Brazil many years earlier and vigorously protested the abolition of slavery, Raymonde Bonnetain was part of a generation with different concerns. "What shocked our beliefs and philosophical ideals, she says, was to see Whites buying, owning and selling Blacks" (p.68). Now was the time to bring French civilisation to the slaves who had been set free.

It is thus to her dismay that she discovered, soon after setting foot in Africa, that slavery was still big business in the colonies. It was so for both Black elites owning slaves as a matter of course and White colonials condoning slave ownership for a variety of dubious reasons. She could understand – or at least come to terms with the fact that, "uneducated Africans" following age-old traditions continued to engage in slave-trading, but she strongly disapproved of the colonial officials and military's pragmatic approach, leniency and even active support to the trade. For example, the prospect of "securing captives" (p.77) during the "pacification" of Sudanese villages was possibly the main incentive for some African youths to enlist in the "regular" French army, especially when they knew they would not be paid. But positing that the allocation of slaves caught in battle could be used in lieu of paying wages to the local recruits was not acceptable in her view. "Emotional or not, pious or not, a woman will never share men's resignation in the face of slavery's despicable nature and murky motive" (p.76), she says. Military expediency was not in line with the author's sense of morality, nor was it with France's republican ideals and "civilising mission".

Raymonde Bonnetain's ideological and religious rejection of slavery did not entail a belief in race equality, though. The pseudo-scientific belief in Africans' inferiority had become the main plank of white imperialism and the year-long sojourn of the author in Africa did not change her racist assumptions: "The Negro from Sudan was a pack animal, nothing more!" (p.81). It is true that on a few occasions, her observations lead to an appreciation of the skills of the people she encountered and she makes a few positive comments here and there: Some young girls are "pretty and cheerful" (p.19); the music of the griots is enjoyable (p.170); children are rather intelligent (p.272), the way people clean their teeth is ingenious (p.274), some are clever at building snares to catch partridges (p.321). These remain incidental, however, as all the racist stereotypes engineered by academe, politicians and socialites in order to justify the exploitation of Africa are surfacing at regular intervals throughout the narration: Black people only understand force, they are all the same, inferior beings, unreliable, lazy ... and a sentence summarizes the author's position on the matter: "In religion as in everything else, the Negro are only monkeys" (p.286).

An interesting aspect of the book concerns seven year old Renée Bonnetain who is much more open-minded than her parents. "Nothing surprises her and she is amused by everything." (p.104). She enjoys the long journey upstream on the Senegal River – 1029 km separate Kayes from Saint-Louis (p.45) –, plays with her dog and is quick to befriend people around her. When the family settles in Kayes, she takes reading tuition with a Quartermaster Sergeant and amuses herself with her toys, but she soon becomes bored and looks with envy at the children playing on the street. Sneaking out of the house, she soon began interacting with her new friends. That, of course, did alarm her mother as "these little brats, aged seven or eight, were only covered with their amulets and charms" (p.145). "Even given the fact that we were in Africa," she adds, "it would have been difficult to tolerate such friends" (p.145). Thus her resolve to find some suitable company for her daughter and, pushing aside her remorse and principles about purchasing another human being, she decides "to buy her a black doll, a living doll, a little slave who I would manumit, polish up and look after", she says. (p.146). A young girl is thus bought from a shady slave-trader and becomes Renée's appointed friend. Educated henceforth like a little French girl, Belvinda does not take long before she adopts the beliefs and attitudes of her host family towards Africa, and loses touch with her Sudanese origins, language and history. Upon returning to France with the Bonnetains, "she no longer knows a single word of Sudan languages and, the author says, she is adamant she doesn't want to go back among these 'dirty Negros'. (sic!)" (p.376).

Like many of her contemporaries, the author believes strongly in the "civilising duty" of France and she cannot understand why her Government does not seem interested in developing the colonies; why instead of fostering a vibrant community that brings the best of French civilisation to Africa, did they accept substandard standards, goods and services ? "Oh yes, travelling makes one wiser", she says disillusioned upon discovering that most French traders and companies are manufacturing inferior goods with the express purpose of exporting them to the Colonies. "The day of this revelation, she adds, some gossip-mongers . . . . stated further that the deplorable practice consisting of disposing of old stock, waste and scrap overseas was not limited to our manufacturers. In the eyes of the State, they said, not only old disused carriages were good enough for the colonies, but also some discharged or unfit employees" (p.27).

Compared with the English approach to colonization, she suggests, France is not performing well and she should change her approach, encouraging women to settle in the colony with their husbands; investing in roads, schools and hospitals instead of the army; building houses, stud farms, inns and carriages suited to the climate; facilitating mail exchange between France and Sudan; providing efficient medical assistance to the people sent to the colony and often left to die for want of basic medical support; limit military campaigns, excessive taxation of African villages and onerous requisition of carriers for countless expeditions; long is her list of practical interventions that could have made a difference, but political expediency, administrative inertia and individuals' idiosyncratic pursuits were strong impediments to change.

Paul Bonnetain was an ex-army man cum author and journalist reporting on military life and colonial matters, but the terms of his mission in Sudan is not very clear from his wife's account. She puts more emphasis on her husband's hunting activities and, at times, harsh treatment of their Black employees than on his official duties. But whatever his mission might have been, he was elevated to the position of Sudan Director of Indigenous Affairs in 1894, upon his return to France.[1] This nomination did not change the fate of the Sudanese population that only worsened as the demands of the colonial administration increased in direct proportion to the expanding number of French military men, officials, overseers, merchants, missionaries and adventurers of all kinds who moved subsequently to every nook and cranny of the colony. The systematic exploitation of Sudanese human and natural resources was in full swing and resistance to the invading forces continued to be emasculated by mass killings of civilians, ruthless military expeditions and the enthronement of a local stooge.[2]

The promotion of Paul Bonnetain that was already rumoured during his sojourn in Sudan created a stir among the military – and especially in the quarters of Colonel Archinard who was in charge of Sudan. As argued by Raymonde Bonnetain, the prospect of a civilian taking over the reins of government meant an increased scrutiny of military operations and reduced opportunities to wage glorious battles that would win the Colonel a couple of stars. Thus his determination to keep Bonnetain at arm's length and his steadfast resolution to cut short the interference of outsiders: "Colonel Archinard did not want, no, he did not want at all my husband to look over his shoulder" (p.204), she says. Thus the Colonel leaving Kayes surreptitiously with his men during one of Paul's short absences. He needed a conquest and was determined "to break down a few tatas" (p.204) (fortifications surrounding African villages) in spite of the specific instructions of the Ministry ordering "pacifying troops" only to engage in fighting in the case of direct provocations (p.204).

His decision to defy orders from Paris [3] paid off as he was promoted to the rank of Brigadier General in 1896, – even if it was amidst much controversy – and in 1904, he became a four star general in charge of the whole colonial army corps. Eventually, his contribution to the "pacification" of Sudan was enshrined in French Official History when he was awarded the "Grand'Croix", that is the highest level of the French Order of the Legion of Honour. Arguably, Raymonde Bonnetain's comments about the unconscionable ferocity and exactions of Archinard's military campaigns in Sudan were mainly based on hearsay that did not provide the hard facts validating historical interpretations; yet the tragic ending of the Voulet-Chanoine Mission in 1899 testifies to military officers' propensity to ignore Paris' directives and to engage in the mass killing of unsuspecting town and village inhabitants in order to put African territories "under French protection". No doubt captain Voulet would have been promoted like the others for his "pacifying" endeavours, had he not been accused of atrocities by one of his men whose complaint ended up in the Parisian press and provoked a major popular outcry. That prompted the government to send another officer after Voulet to relieve him of his command. True to form, Voulet refused to submit to Colonel Klobb – the officer who tracked him for over two thousand kilometres to relieve him – and eventually shot him. This painful incident reported by Mrs Klobb in her book Un drame colonial. A la recherche de Voulet. Mission Klobb-Meynier [4] not only testifies to the thin line that separates the heroic and decorated figures of colonisation from the villains abandoned to public obloquy for political expediency, but it also hints at the ill-documented string of massacres that have been expunged from French history and replaced by the vague and misleading term of "pacification".

Raymonde Bonnetain discovered Africa with some degree of astonishment. As her journey progressed, she slowly realised that the inferno depicted by well meaning friends before she left France did not describe appropriately the country she was discovering day by day.[5] Travelling thousands of kilometres by train, boat and on horseback was exciting, and meeting people along the way enjoyable, even if the accommodation was often rudimentary, the heat oppressive and female companionship non-existent. What came to her as a shock, though, was the mismanagement of the colony, the antagonism between the Navy and the Army, the deprivation of the young men sent to Sudan and the unnecessary hardship they suffered for want of a proper management of resources. She was not afraid to ask the difficult questions, to air her view publicly and to complain directly to the Ministry when necessary.

Raymonde Bonnetain's candid observations of Sudan is a severe indictment of colonial mentality. [6] Sudan was not the most hospitable place on earth, she argues, but what made it so deadly for the young men sent over there to "pacify" the region, was mainly due to mismanagement, military abuses, secrecy, idleness, oversized egos and political ineptitude: "I expected fevers, sunstrokes, hostility from the sky and the earth rather than the enmity of fellow men, she says; but it was the latter that we had to deal with . . . . I am sensing that there were fewer quagmires in the bush than booby traps laid down in offices. That makes me sad" (p.100). That also led her testimony to vanish from French collective memory and the re-edition proposed by l'Harmattan in 2007 is certainly timely.[7]

Jean-Marie Volet

Notes

1. Paul Bonnetain published a collection of short stories inspired by his journey to Sudan titled "Dans la brousse : sensations du Soudan". Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, éditeur, 1895. The first short-story of the compilation, "Le confrère" [the colleague], is very much worth reading. (Sighted on Gallica, Bibliothèque nationale de France, January 18, 2012).

2. Jean Rodes wrote in 1899: "Nous sommes au Soudan de mauvais administrateurs, de tristes propagateurs de civilisation et de déplorables juges . . . . L'armée n'a su donner aucun essor ni à son agriculture, ni à son commerce, ni à son exploitation industrielle" (Cited by Jean-Marie Seillan. "Aux sources du roman colonial. L'Afrique à la fin du XIXe siècle. Paris: Karthala, 2006, p.365, note 26.)

3. See A. S. Kanya-Forstner. "The Conquest of the Western Sudan". Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1969. (Notes by Jim Jones at https://courses.wcupa.edu/jones/his311/archives/sec/kanya3.htm sighted August 20, 2012).

4. Mme Klobb. "Un drame colonial. A la recherche de Voulet. Mission Klobb-Meynier". Paris: Nouvelles editions Argo, 1931.

5. Nine pictures of the Bonnetain's family in Sudan are available online at:

https://bspe-p-pub.paris.fr/Portail/Site/ParisFrame.asp?lang=FR (Sighted August 20, 2012). Open « Collections numérisées » ; type « Bonnetain » in « Recherche par mots » (Annie Metz, Conservatrice en chef, Bibliothèque Marguerite Durand].

6. "Le roman des voyageuses". Raymonde Bonnetain (1868-1913). Video et commentaire de Françoise Lapeyre. https://leromandesvoyageuses.fr/fiche_voyageuse.php?id=11&PHPSESSID=25037c8a1d294affd2388def96ed0da0&language=en&PHPSESSID=25037c8a1d294affd2388def96ed0da0 (Sighted August 20, 2012).

7. Raymonde Bonnetain. "Une Française au Soudan: sur la route de Tombouctou, du Sénégal au Niger" (1894). Paris: l'Harmattan, 2007. Collection "Autrement mêmes". Présentation de Jean-Marie Seillan.

[Other books] | [Other reviews] | [Home]

Editor ([email protected])

The University of Western Australia/School of Humanities

Created: 1-September-2012.

https://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/revieweng_bonnetain12.html