|

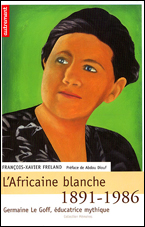

NOT TO BE MISSED " L'Africaine blanche (1891-1986) : Germaine Le Goff, éducatrice mythique", a biography by François-Xavier FRELAND Paris : Editions Autrement, 2004. (160p.). ISBN : 2-7467-0570-2.

|

Ce compte rendu en français |

Germaine Le Goff's life-story is worth discovering. It stretches over the best part of the 20th century and shows her strong determination to provide African girls access to school. In the context of an overwhelming lack of concern by colonial administrators and a strong resistance by the local population towards French educational ideals, Mrs Le Goff arrived in Djenne, Mali, in 1923. In 1938, she became the director of the first African Teacher's College open to female students in Senegal and she passed away in France, aged 95. Her diary, memoirs and abundant correspondence have not been published to date, but François-Xavier Freland's biography, based on this unpublished material, offers a engaging portrayal of this amazing educationalist.

Germaine Le Goff was born in 1891 into a very poor family of fishermen in Brittany. At a time of fierce animosity between the French State and the Catholic Church, the anti-clericalism of her parents and the financial help of an Uncle gave her the opportunity to attend the local Teachers' College and to became a primary schoolteacher. After a few years teaching locally, she left for the colonies, mainly because her relationship with the local priest had become increasingly strained, the antagonism of the local intelligentsia difficult to bear and the Republican ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity impossible to uphold. As she wrote in her memoirs on the eve of leaving for Africa : "Goodbye malicious clergyman ... you have shown us that some predicaments have no solution when you are poor, that the word freedom has no meaning when your are enfeoffed to a rich and powerful man or reviled by a wrathful dictator like you, Reverend Priest of the Réguiny Parish..." (p.36).

Germaine Le Goff was born in 1891 into a very poor family of fishermen in Brittany. At a time of fierce animosity between the French State and the Catholic Church, the anti-clericalism of her parents and the financial help of an Uncle gave her the opportunity to attend the local Teachers' College and to became a primary schoolteacher. After a few years teaching locally, she left for the colonies, mainly because her relationship with the local priest had become increasingly strained, the antagonism of the local intelligentsia difficult to bear and the Republican ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity impossible to uphold. As she wrote in her memoirs on the eve of leaving for Africa : "Goodbye malicious clergyman ... you have shown us that some predicaments have no solution when you are poor, that the word freedom has no meaning when your are enfeoffed to a rich and powerful man or reviled by a wrathful dictator like you, Reverend Priest of the Réguiny Parish..." (p.36).

At first, life in Djenne seemed like heaven on earth compared to the harsh conditions experienced by the family in Brittany. There were no priests fighting unholy wars from the pulpit, a large and comfortable dwelling and a few servants taking care of household chores. However, teaching the local youth and, in particular, young girls who were entrusted to her care, was far more challenging than she had anticipated: none of her pupils spoke French, she did not speak local languages, and the famous 3Rs underpinning the French curriculum did not seem relevant to the needs of the local female population. As she wrote in her memoirs: "I soon understood that teaching – the same way as in France – girls who hailed from totally illiterate milieux was putting the cart before the horse. How useful could be the knowledge I was teaching in a place such as Djenne where there were no books, no newspapers and not a single shop selling pen and paper. What was the point of learning to read when there was nothing to read anyway? What was the point of learning to write if one had no-one to write to? Why teach operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication and division to young girls who probably would never have more than a few cauris in their possession when they go to the markets ... Wasn't it fanciful to teach these skills to young girls who would have to take the path followed by their mothers and all African women since time immemorial?" (p.47).

This critical self-appraisal of her role as an educator led her to adapt her teaching to the real challenges facing her pupils. She encouraged parents to send their daughters to school and began training assistant teachers who could take care of the youngest girls, as the colonial administration was unable to provided more teachers for its "civilizing mission". Her initiative attracted praise from some of her superiors and in 1926, the family Le Goff was promoted to a new posting at the Lycee Faidherbe in Saint-Louis. The city was modern, the streets busy and the aviator Jean Mermoz had just established an air link between Senegal and France but, unfortunately, life in the lycee was something of a nightmare. The headmaster was incompetent, students unruly and the teachers' quarters very poor.

However, these substandard conditions did not prevent Mrs Le Goff from pursuing her interest in women's education. She wrote a little book titled "Mamadou et Kadidia" that illustrated to her students the virtues of good behaviour and she kept lobbying the colonial administration for better educational opportunities for girls. In her view, "African women did not exist in the coloniser's mind", yet progress was not possible without equal opportunities between the genders: it was not possible in France, it was not possible in Africa, nor in any other part of the world. A new posting in Dakar in 1932 allowed her to develop further her educational credo based on tolerance, equality and freedom of religious beliefs, a conviction that pitched her against Dakar's Catholic Bishop, but unlike ten years earlier, she was no longer a young teacher easily bullied by a parish priest.

France's change of Government in 1936 brought new blood and opened a new chapter in Mrs Le Goff's industrious career. In 1938, the Colony's Governor General gazetted the creation of a Teacher's College for African Women in Rufisque and Mrs Le Goff was appointed founding Headmistress of the School. From the outset, she decided to recruit aspiring women teachers from across the whole of the French African colonies. Some forty young women were selected and many more would follow in subsequent years. Mrs Le Goff's speech, delivered thirty years later, on the occasion of an invitation by her former students – who called her affectionately "Mamie Le Goff" – summarises very well her aims:

"I am proud of my daughters. No longer my young students, but women who are now mothers, citizens of independent countries. Wherever fate has decided to send them, I know that they are accomplishing diligently and competently the charge entrusted to them. I know that their children are moving upward! But this new generation should never forget that, in 1938, my goal was not to generate women intellectuals but rather progressive women who could educate the masses through their personal energy and school education. They should never forget, these children of my daughters, that when I was seeing the latter leave our family home in Rufisque, I knew that they were about to plunge into milieux that were often hostile and did not accept, at the time, the evolution of African women ... Already I had become aware of that issue when, in 1923, I was opening the first school for girls in Djenne. If I deserve any credit, it is for my engagement with education rather than under-education for under-developed countries ... I understood that "my African women" possessed qualities deep within themselves, possibilities that they had to discover for themselves and acknowledge in order to exploit these qualities as best they could. They've done it." (p.146)

Difficult years followed when World War II broke out. The war effort drained the country's resources and left the student-teachers and their Director with very little help, financial and otherwise. Mrs Le Goff's open criticism of Petain's Vichy Government did not help either, but the impression she made on her pupils, in spite of harrowing conditions, was enormous and her loyalty to them exemplary. To mention just one example, her unsuccessful plea in favour of two students who were summoned by the disciplinary committee of the School because they fell pregnant. Her intercession shows her determination to put the good of students before rules and bigotry: "Some demanded the total expulsion of these two young apprentice-teachers, she said. They are accused of falling pregnant in a milieu where marriage is a simple transaction between two families who agree on a dowry ... Young women who don't even understand their mistake are being blamed. It is an error to judge everything in relation to French custom and on this occasion this leads to an injustice." (p.112)

This non-sectarian approach paid off and in subsequent years, a string women teachers who studied in Rufisque would make good and become eminent African personalities in various fields of newly independent countries. Among them, the Guinean, Jeanne Martin-Cissé and the Ivoirian, Jeanne Gervais were among the very first female Parliamentary Ministers in any African country; the Senegalese journalist Annette Mbaye d'Erneville and the celebrated writer Mariama Bâ, not to mention the anonymous Togolese primary teacher who wrote a short autobiography titled "Je suis une Africaine...j'ai vingt ans" [I am an African woman ... I am twenty] in a newspaper published in Dakar in 1942 [see her text at : aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/dakar_jeunes1.html]. There were many other pioneers who taught in remote villages and marked the beginnings of a major shift toward gender equality. Mrs Le Goff 's life-story is very worthwhile reading. It tells of an important chapter in the elimination of female illiteracy and the subsequent broadening of opportunities, duties and responsibilities in contemporary African society.

Jean-Marie Volet

[Other books] | [Other reviews] | [Home]

Editor ([email protected])

The University of Western Australia/School of Humanities

Created: 06-July-2009.

https://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/revieweng_legoff09.html