|

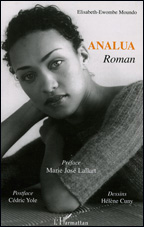

NOT TO BE MISSED "Analua", a novel by Elizabeth-Ewombè MOUNDO Paris: L'Harmattan, 2005. (156p.). ISBN: 2 7475 8329 5.

|

Ce compte rendu en français |

Analua is a tale of love, fears and primeval attachment to the country one calls home. When Analua comes into the world in a small island of Cape Verde, her birth is celebrated with a flurry of festivities. But the good times are short-lived and a long and devastating spell of drought soon follows, bringing ruin and devastation to the achada San Felipe. Hunger kills many and the survivors have to abandon the village. Analua seeks refuge with her grandmother Maluda in a town nearby but, unfortunately, tragedy strikes again in her new place of residence and her departure from the country that follows does not hold promise.

Analua is a lively, good-natured and clever individual with the gift to express profound ideas and feelings with simple words, which her friend João is quick to note: "I had the ambition of becoming a writer ... to capture the magic and the emotion of every-day language. But it was her, I was now realising, who was unveiling that magic" (p.80). Moreover, she is a dutiful member of the community who abides by the elders' decisions with no recrimination, even when she gets a raw deal, as is the case when she is married to a hideous and decrepit old man.

Analua is a lively, good-natured and clever individual with the gift to express profound ideas and feelings with simple words, which her friend João is quick to note: "I had the ambition of becoming a writer ... to capture the magic and the emotion of every-day language. But it was her, I was now realising, who was unveiling that magic" (p.80). Moreover, she is a dutiful member of the community who abides by the elders' decisions with no recrimination, even when she gets a raw deal, as is the case when she is married to a hideous and decrepit old man.

Like many teenagers who had to endure a similar predicament, Analua survives the devastating blow to her hopes of marrying someone she could love and she accepts, as best she can, to serve her husband "with the honesty expected from a girl with no dowry, but brought up in a respectable family" (p.61). This example of discipline and self control would have pleased her folk, but it concealed well another side of her personality. Behind the biddable young woman, one can also discover a determined and inquisitive person who is not prepared to let traditional and divine wisdom go unchallenged in all circumstances.

From early in life, Analua had been curious, pestering her grandmother Maluda with questions about the nature of things and the quirks of fate guiding her family's destiny. But there are questions even a wise old woman cannot answer: that even the parish priest cannot answer. Questions that have no logical answer. And while the dutiful daughter could understand the reasons that pushed her grandmother to marry her to a man she could never love, the rational thinker in her cannot come to terms with the death of her parents and other members of her family. The local priest is extolling God's will, but from the time of her parents' demise, she has known that "God had abandoned them" (p.45). Ever since, she says, she had not been "on friendly terms" with Him (p.123). And while she respects priests as human beings, she despises their blind faith and finds no solace in their invitation to pray. She cannot accept the idea, as she is told, that it would be presumptuous to ask the Almighty for the reasons behind His deeds. There are things she is not prepared to accept, and the trail of deaths she leaves behind her is one of them.

When her grandmother, her husband and her baby pass away in quick succession, she realises that going to Mass and obeying her elders led her nowhere. All the people she cared for are gone and she finds herself alone, in shock and wondering why her own life has been spared. To all and sundry she looks as though she is resigned to this harsh reality, but deep within her torments and uncertainties are taking their toll. As modern psychology would put it, she is suffering from some kind of post-traumatic stress disorder that prevents her from letting go and building new, meaningful relationships with others. And as time passes by, she becomes increasingly convinced that, for some unexplained reasons, some wicked gods are punishing by death all those who dared to love her.

Her brief liaison with João, a young teacher with whom she falls in love shortly after she leaves Cape Verde, is certainly the most poignant and heartbreaking expression of her condition: they are made for each other and following her traumatic experience with the repulsive wretch she had been obliged to marry, Jaoa seems to be heaven-sent, one who could reconcile her with life. "Upon meeting João", she says, "I discovered that something had been missing in my life, that the journey had been long, but that I could eventually empty my suitcases... I was discovering life, I was at peace with my demons" (p.127).

But this relationship comes to an abrupt end as Analua's mental ailment catches up with her. The fear of losing her lover, the same way she lost all of her loved ones before, grows everyday more acute and, eventually gets the better of her. João dreaming of an old woman with a cynical smile coming to see them is the last straw: she sees it as a terrifying sign that death is again on the doorstep. Hence her hasty departure, without a word of explanation to her companion, because she is convinced that it is the only alternative if she wants to spare the young man's life: She's running away in order to spare his life. That of course has tragic consequences for the young man who is at a loss to explain Analua's sudden disappearance. Unaware of his lover's mental condition, he wonders what went wrong and cannot bring closure to a relationship that was going so well. The story does not say if João managed to come to terms with his grief, but it reveals that it takes years for Analua to reconcile herself with the idea that life and death are randomly apportioned, that she is not liable for the death of her parents, but a victim of fate. As her friend Cardoso – who is seen as a sorcerer in the village – tells her: "People interpret signs according to their own beliefs ... and they attempt to match these signs with their own desires" (p.135). One might argue that they also do so according to their forebodings and fears, as Analua's obsession shows only too well.

For better or for worse, impressions and perceptions are therefore far more important to Analua than hard, cold facts. The death of her decrepit old husband did free her from family chores and matrimonial duties. It provided her with an unique opportunity to move away from the village and to seek her fortune elsewhere. Yet, she did not see this passing as a liberation, but rather as an echo of the heartbreaking separations she suffered in her earlier life, a confirmation that death was deliberately targeting everyone close to her. It is neither physical hardship nor personal ambition that determines her feelings. It is "her compounded sorrow" (p.87), her intimate belief that she is the one attracting death sentences upon everyone becoming close to her. She cannot see herself as a victim of fate, but always interprets her survival – and occasional good fortune – as additional proof she is the one who is causing the suffering and disappearance of others.

The demons inhabiting the main character give a dark undertone to the novel, but Analua is not a book only diffusing gloom and doom. It also proposes a resolutely forward looking approach to life and emphasises the complementarity of the good and bad in everything. Water that is so essential to the survival of the achada is also killing many people when floods inundate the fields, taking houses away and drowning people. So too, a strict compliance to elders' rules is ensuring social cohesion and a strong sense of belonging, but it leaves young girls with no say with regard to their future. As for sorcery that condemned so many innocent people to opprobrium and even death, it was a means to address issues that were beyond human comprehension, to provide an answer where human logic and experience could provide none. Thus Cardoso becoming a sorcerer after losing his eyesight and admitting to Analua, with tongue in cheek: "I just had to let people believe what they already believed" (p.135).

Analua is both a testimonial to the resilience of the Cape-Verdians of yester-years and an invitation to readers to discover a harsh and forbidding land that can also be a paradise that invites a celebration of life. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder and, for Analua, nothing can better soothe the trauma caused by the lethal forces unleashed on the island by the elements than the exhilarating and regenerating power of life that always has the last word. In the aforementioned interview, Elizabeth-Ewombè Moundo said that, in her opinion, "cross-examining culture was the only key to an understanding of human beings" [1]. Her innermost exploration of Analua's psyche eloquently proves the point. An interesting book, highly recommended.

Jean-Marie Volet

Note

1. Mathieu Mbarga-Abega. "Elizabeth-Ewombè Moundo commente sa large expérience". "Amina" 485 (septembre 2010), pp.18-19.

[https://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/AMINAewombe10.html]

[Other books] | [Other reviews] | [Home]

Editor ([email protected])

The University of Western Australia/School of Humanities

Created: 01-May-2011.

https://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/revieweng_moundo11.html