|

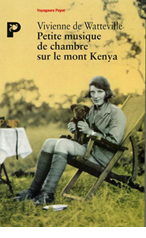

NOT TO BE MISSED "Speak to the Earth", Part II, "The Mountain (Mount Kenya)", a personal history by Vivienne de WATTEVILLE. New York: Harrisson Smith and Robert Haas, 1935. (pp.209-335).

|

Ce compte rendu en français |

Speak to the earth by Vivienne de Watteville was published in 1935 in English and in 1936 in a French translation. Part II of the volume, titled "The Mountain (Mount Kenya)", is not only a good read, it is also one of those great books that would easily make it into the haversack of the legendary castaway stranded on a desert island. It is full of wisdom, speaks of Nature, solitude, happiness, the human spirit and emphasises the fact people are not single "units of nothing, drifting aimlessly" (p.328).

Vivienne de Watteville's accomplishment is quite surprising as the first book she wrote about her African experience would be best forgotten.* She had accompanied her father on a hunting expedition and her travelogue is soaked in blood. It records her father's bold and enthusiastic slaughtering of big game until he was mauled by a lion and his gun silenced for ever. How someone with such a background could produce, just a few years later, the most poignant plea for animal protection and respect for the environment may be hard to explain. Yet, upon reading the beginning of the volume Vivienne de Watteville published after her second journey to East Africa, this apparent contradiction is easier to understand: "Before", she writes, "I had gone out with my father to make a collection of the fauna of East Africa for the Berne Museum. This had been his dream, which we had long shared and saved for. But my own private dream had always been to go into the wild unarmed and, in some unforeseen way, to win the friendship of the beasts. I envied none as much as Androcles, who by so trifling an incident as meeting a lion with a thorn in his paw (coupled with his resource in pulling the thorn out) gained the lion's lifelong devotion. And now I was going back in my own way" (p.5).

Vivienne de Watteville's accomplishment is quite surprising as the first book she wrote about her African experience would be best forgotten.* She had accompanied her father on a hunting expedition and her travelogue is soaked in blood. It records her father's bold and enthusiastic slaughtering of big game until he was mauled by a lion and his gun silenced for ever. How someone with such a background could produce, just a few years later, the most poignant plea for animal protection and respect for the environment may be hard to explain. Yet, upon reading the beginning of the volume Vivienne de Watteville published after her second journey to East Africa, this apparent contradiction is easier to understand: "Before", she writes, "I had gone out with my father to make a collection of the fauna of East Africa for the Berne Museum. This had been his dream, which we had long shared and saved for. But my own private dream had always been to go into the wild unarmed and, in some unforeseen way, to win the friendship of the beasts. I envied none as much as Androcles, who by so trifling an incident as meeting a lion with a thorn in his paw (coupled with his resource in pulling the thorn out) gained the lion's lifelong devotion. And now I was going back in my own way" (p.5).

What makes the narrator's pursuit of her dream doubly interesting for the reader is the fact that her quest for peace with the animal kingdom is not an end in itself. It belongs to a bigger project aimed at teasing out the meaning of life and death, something the author suggests is not possible until the noise and bustle of human activity have faded away. "When man is near", she says, "Nature shrinks unobtrusively into the background to become merely a setting. When man passes on, Nature comes to life again... and you find yourself in the midst of a silence, not empty or lonely but full of the poetry of the all important business of life" (p.241). A remote cabin pitched on the slope of Mount Kenya at an altitude of 10.000 feet provided her with the ideal place from which to rediscover the world and the small things that are the salt of the earth. Those things, she says, "led me to first principles" (p.319).

Simplicity is certainly one of these fundamental principles and it applies to every aspects of her life. Yet, her spartan accommodation, frugal day-to-day needs and long walks to the highest peaks of the region allow her to value differently her relationship with the world. She realises that big emotions and happiness are born of little things that do not last: the break of day in the romantic yet freezing Hall Tarn on the edge of a thousand foot precipice (p.248), "a fairyland of flowers, ferns and moss beside a little waterfall" (p.224), "the spray of golden flowers hanging against the golden gloom and a stream running by like crystals over amber" (p.224), or "the little birds in choirs of three or four always singing the same two bars out of the Brahms Piano Quintet" (p.318). One gets a sweeter thrill of joy from these things, she says, than from the load of responsibility of possession because, for the moment you possess a thing, you put it behind you, locked safely in the treasure-house, and turn your face towards new conquests, new acquisitions (p.272).

According to 21st century "popular wisdom", the world is changing faster and faster, but upon reading Vivienne de Watteville - who wrote almost a century ago - one gets the impression that one needs only scratch the surface to see that human interrogations, aspirations and existential quests have not changed. Millions of miles of new barriers have been erected in the world and treasure-chests are full to the top, but people are still chasing the same ideals, confronting the same fears and flirting with the transience of happiness in the same way they always have: ergo, the modernity in tone and concerns of many passages of Speak to the earth. The drawbacks of fast travel between different locations is but one of the many splendid examples that ring true in the 21st century, both literally and metaphorically speaking. The pleasure of reaching the final destination becomes secondary to the satisfaction of making the journey.

"To go by car over the Thika—Fort Hall—Meru road", she says, "the same road we had tramped along in the heat and dust over five years before, was a curious and poignant experience... What before had been a whole day's trek now took me no more than a bare hour in the car. I could not reconcile myself to that. There was something almost callous about it... The advantages of a car are not to be dismissed lightly, yet I think they are dearly bought. You may be superior to the road which before held you at the mercy of its every whim and caprice, but this superiority sends you through the country a complete stranger. For when all is said and done, however long the road may have seemed afoot, it was a companion whom you came to understand and love" (pp.214-15).

Many of the dilemmas besetting Vivienne de Watteville are still puzzling today: What is the value of doing things ? Where is the limit between courage, determination and foolishness ? How can one long to make friends with the animals and yet eat meat ? Why do we persist in dividing instead of uniting while earth and spirit proclaim with a thousand tongues that all is fashioned from the same material, shaped by the same inspiration and animated by the same life-breath ? (p.328). Short of providing her with definitive answers, the African vastness gave the author the conviction that these were the type of questions one should ask in order to make some sense of the contradictions and mysteries of life, a life that comprises not only living creatures, great and small, but also the cascades and the icy slopes of Mount Kenya, the rocks and the stars...

Vivienne de Watteville's Africa has nothing in common with the dark, exotic and hostile continent set upon by her father and his like. To her, it is a place where she could hear her heart beat in unison with the rest of the world and find out that "one is never lost or alone as long as one can claim kinship with everything that is" (p.328).

Jean-Marie Volet

Note

* Vivienne de Watteville. "Out in the Blue". London: Methuen & Co, 1927.

(This review is based on the French translation of the novel, titled Petite musique de chambre sur le Mount Kenya, but page numbers relate to the first English edition).

[Other books] | [Other reviews] | [Home]

Editor ([email protected])

The University of Western Australia/School of Humanities

Created: 6-March-2009

https://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/revieweng_watteville09.html