|

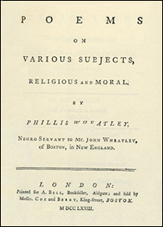

NOT TO BE MISSED "Poems on various subjects religious and moral", Poetry by Phillis WHEATLEY London: A. Bell Books, 1773, (128p.).

|

Ce compte rendu en français |

Phillis Wheatley was the very first African female author to publish a book and her collection of poetry Poems on various subjects religious and moral1 – published in 1773 – marks the beginnings of African-American literature. Phillis Wheatley whose real name was, possibly, Aminata, Maïmouna, Fatou or any other name common in Senegal, was born in West Africa around 1754. Aged about seven, she was abducted from her home, cut off from her family and transported on the ship Phillis to the United States of America where she was sold as a domestic slave to the Wheatley family.

Mrs Wheatley soon realised that the frail little maid she had bought was exceptionally gifted and better suited to intellectual pursuits than household chores, thus she decided to have her tutored in reading and writing. At the age of eleven, Maïmouna-Phillis was writing her first poems and two years later one of them had been accepted for publication by the Newport Mercury. By 1773, Phillis Wheatley was a well-read intellectual and a fully fledged poet. She had a printed volume of poetry to her name and a worldwide reputation while still barely twenty.

Mrs Wheatley soon realised that the frail little maid she had bought was exceptionally gifted and better suited to intellectual pursuits than household chores, thus she decided to have her tutored in reading and writing. At the age of eleven, Maïmouna-Phillis was writing her first poems and two years later one of them had been accepted for publication by the Newport Mercury. By 1773, Phillis Wheatley was a well-read intellectual and a fully fledged poet. She had a printed volume of poetry to her name and a worldwide reputation while still barely twenty.

Publishing a book written by a Black female slave, though, had not been an easy feat. The Wheatleys did not get enough support in Boston to bring the project to fruition and they had to look outside America to find a patron and a publisher. Such people were found in London where the Countess of Huntingdon and the bookseller A. Bell accepted the challenge on the condition that some of Boston's dignitaries would provide a certificate of authenticity of the poems. Such a document was included in the first edition, signed by eighteen people holding most influential positions in Boston society.

As the publication of the book approached, Phillis Wheatley was invited to go to London to promote her work and she arrived there in June 1773. A long list of social engagements awaited her and she was to meet "the cream of the cream" of British intelligentsia. Soon after her arrival, a copy of her poem "A Farewell to America" was published in The London Chronicle but only a few months into her London sojourn a letter advising that Mrs Wheatley was gravely ill reached her. Phillis was told to return home and she did so, cutting short her engagements. By September 1773, she was back on American shores. A slave had to submit to the orders of her mistress.

The twist in the tail is the fact that Phillis Wheatley could have legally stayed in London against the demands of the Wheatleys for as long as she wished. The previous year, Lord Mansfield, Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench had ruled that once in England, a slave could not legally be forced back to the colonies by his or her master. Phillis had met the London abolitionist Granville Sharp who had been instrumental in Lord Mansfield's ruling and it is almost certain that Phillis knew that the option of staying in London for as long as she chose was open to her. Why then did she decide to return to Boston ? The answer is not entirely clear. Was it, perhaps, because the Wheatleys promised her manumission if she returned as they were keen to see her soothing the pains of an ailing Mrs Wheatley ? No one knows the answer, but the fact is that one month after her arrival home, her manumission papers were signed, sealed and delivered. Phillis Wheatley was free.

In the meantime, Bostonians' overall attitude toward Blacks – an that included the very few who were legally free – had not changed. Phillis Wheatley realised that fact when she attempted to publish the sequel to her first volume. Her best efforts were still rejected by publishers in spite of flattering comments from both home and abroad. To mention just two of the many people offering generous views, George Washington wrote to her in 1776 : "... I shall be happy to see a person so favoured by the Muses, and to whom nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations"2, and Voltaire mentioned her in a letter dated 1774, saying that "Fontenelle was wrong in arguing that there were no poets among the Negroes: currently, there is indeed a Negro Poetess who is writing very good English verse".

Of course Phillis Wheatley also had some detractors; people like Thomas Jefferson considered that "Religion indeed has produced a Phillis Wheatley, but it could not produce a poet"3; some other critics, past and present, found her "hopelessly irrelevant to any meaningful Black-American thought"4, but the truth of the matter is that it took America a great many years to come to terms with the idea that a genius could not only be black, but also a female.

The passing of Mrs Wheatley in March 1774 deprived Phillis of the help of a powerful friend and benefactress. Difficult years followed: an unhappy marriage, the repeated rebuff of the printers, her poor health, the death of her children and her eventual wretched conditions of life; all these factors contributed to her early death in 1784, aged only thirty.

It cannot be denied that the Wheatleys offered Phillis the best education any young lady could get and they fostered her exceptional talents. However, one should not lose sight of the tragedy that led the young girl to Boston in the first place. As Phillis Wheatley wrote in one of her very few autobiographical poems:

I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate

Was snatch'd from Afric's fancy'd happy seat:

What pangs excruciating must molest,

What sorrows labour in my parent's breast ?

Stell'd was that soul and by no misery mov'd

That from a father seiz'd his babe belov'd:

Such, such my case. And can I then but pray

Others may never feel tyrannic sway ?5

Phillis Wheatley Complete writings edited by Vincent Carretta is a must read. Beside all the poems written by Phillis Wheatley (published and extant), the volume also includes the correspondence of the author, a few extracts by other African-American writers of the 18th century and an outstanding introduction that contains fascinating analyses and commentaries on Phillis Wheatley's life and work.

Jean-Marie Volet

Notes

1. A facsimile of the book published in 1773 is available in "The Collected works of Phillis Wheatley" (ed. John Shields). Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

2. In "Phillis Wheatley and the origins of African American literature". Limited Commemorative Edition, Boston: Old South Meeting House, 1999, p.23.

3. In "Phillis Wheatley complete writings". (ed. Vincent Carretta). New York: Penguin Books, 2001. "Introduction", p.xxxvi. This re-edition ISBN 978-0-14-042430-0 also includes extant poems not published in the collection and the author's correspondence.

4. In "Phillis Wheatley and the origins of African American literature", p.10.

5. In "Phillis Wheatley complete writings". (ed. Vincent Carretta), p.40.

[Other books] | [Other reviews] | [Home]

Editor ([email protected])

The University of Western Australia/School of Humanities

Created: 22-April-2009.

https://aflit.arts.uwa.edu.au/revieweng_wheatley09.html